The Theosophical Society,

The Writings of Annie Besant

(1847 -1933)

Jainism

by

Annie Besant

Brothers:

We shall find ourselves

this morning in a very different atmosphere from that in which we were

yesterday, and in which we shall be tomorrow. We shall not now have around us

the atmosphere of romance, of chivalry, that we find both in the faith of Islam

and in that of the Sikhs. On the contrary we shall be in a calm, philosophic,

quiet atmosphere. We shall find ourselves considering the problems of human

existence looked at with the eye of the philosopher, of the metaphysician, and

on the other hand the question of conduct will take up a large part of our

thought; how man should live: what is his relation to the lower creatures

around him; how he should so guide his life, his actions, that he may not

injure, that he may not destroy. One might almost sum up the atmosphere of

Jainism in one phrase, that we find in the Sutra Kritănga, [iii,

20] that man by injuring no living creature reaches the Nirvana which is

peace. That is a phrase that seems to carry with it the whole thought of the

Jaina: peace - peace between man and man, peace between man and animal, peace

everywhere and in all things, a perfect brotherhood of all that lives. Such is

the ideal of the Jaina, such is the thought that he endeavors to realize upon

earth.

Now the Jainas

are comparatively a small body; they only number between one and two million

men; a community powerful not by its numbers, but by its purity of life, and

also by the wealth of its members — merchants and traders for the most part.

The four castes of the Hindus are recognized by the Jainas, but you will how

find few Brahmanas among them; few also of the Kshatriyas, which caste seems

wholly incompatible with the present ideas of the Jainas, though, their Jinas

are all Kshatriyas. The vast mass of them are Vaishyas — traders, merchants and

manufacturers — and we find them mostly gathered in Rajputana, in Guzerat, in

Kathiawar; scattered indeed also in other parts, but the great Jaina

communities may be said to be confined to these regions of India. Truly it was

not so in the past, for we shall find presently that they spread, especially at

the time of the Christian Era, as well as before it and after it, through the

whole of Southern India; but if we take them as they are today, the provinces

that I mentioned may be said practically to include the mass of the Jainas.

There is one

point with regard to the castes which separates them from Hinduism. The

Sannyăsî of the Jaina may come from any caste. He is not restricted, as in

ordinary orthodox Hinduism, to the Brahmana caste. The Yati may come from any

of the castes, and of course as a rule comes from the Vaishya, that being the

enormously predominating caste among the Jainas.

And now with

regard to their way of looking at the world for a moment; and then we will

consider the great Being, who is spoken of in western orientalism, not by

themselves, as the Founder.

They have the same

enormous cycles of time that we are familiar with in Hinduism; and it must be

remembered that both the Jaina and the Buddhist are fundamentally offshoots

from ancient Hinduism; and it would have been better had men not been so

inclined to divide, and to lay stress on differences rather than similarities —

if both these great offshoots had remained as Darsanas of Hinduism, rather than

have separated off into different, and as it were rival, faiths. For a long

time among the occidental scholars, Jainism was looked on as derived from

Buddhism. That is now admitted to be a blunder and both alike derive from the

more ancient Hindu faith; and in truth there are great differences between the

Jaina and the Buddhist, although there be also similarities, likenesses of

teaching. There is however no doubt at all, if you will permit me to speak

positively, that Jainism in

Twenty-four of

these appear in each great cycle, and, if you take the Kalpa Sutra

of the Jainas, you will find in that the lives of these Jinas. The life of the

only one which is given there at all fully — and the fullness is of a very

limited description — is that of the twenty-fourth and last, He who was called

Mahăvîra, the mighty Hero. He stands to the Jaina as the last representative of

the Teachers of the world; as I said, He is contemporary with Săkhya Muni, and

by some He is said to be His kinsman. His life was simple, with little incident

apparently, but great teachings. Coming down from loftier regions to His latest

incarnation, that in which He was to obtain illumination, He at first guided

His course into a Brahmana family, where, it would seem from the account given,

He had intended to take birth; but Indra, the King of the Devas, seeing the

coming of the Jina, said that it was not right that He should be born among the

Brahmanas, for ever the Jina was a Kshatriya and in a royal house must He be

born. So Indra sent one of the Devas to guide the birth of the Jina to the

family of King Siddhărtha, in which He was finally born. His birth was

surrounded by those signs of joy and delight that ever herald the coming of one

of the great Prophets of the race — the songs of the Devas, the music of

Gandharvas, the scattering of flowers from heaven — these are ever the

accompaniments of the birth of the one of Saviors of the world. And the Child

is born amid these rejoicings, and since, after His conception in the family,

the family had increased in wealth, in power, in prosperity, they named Him

Vardhamăna — the Increaser of the prosperity of his family. He grew up as a

boy, as a youth, loving and dutiful to His parents; but ever in His heart the

vow that He had taken, long lives before, to renounce all, to reach

illumination, to become a Savior of the world. He waits until father and mother

are dead, so that He may not grieve their hearts by the leaving; and then,

taking the permission of His elder brother and the royal councillors, He goes

forth surrounded by crowds of people to adopt the ascetic life. He reaches the

jungle; He pulls off his robes, the royal robes and royal ornaments; He tears

out his hair; He puts on the garment of the ascetic; He sends away the royal

procession that followed Him, and plunges alone into the jungle. There for

twelve years He practices great austerities, striving to realize Himself and to

realize the nothingness of all things but the Self; and in the thirteenth year

illumination breaks upon Him, and the light of the Self shines forth upon Him,

and the knowledge of the Supreme becomes His own. He shakes off the

bonds of Avidyă and becomes the omniscient, the all-knowing; and then He comes

forth as Teacher to the world, teaching for forty-two years of perfect life.

Of the

teachings, we are here told practically nothing; the names of some disciples

are given; but the life, the incidents, these are all omitted. It is as though

the feeling that all this is illusion, it is nothing, it is naught, had passed

into the records of the Teacher, so as to make the outer teaching as nothing,

the Teacher Himself as nothing. And then He dies after forty-two years of

labor, at Păpă 526 years before the birth of Christ. Not very much, you see, to

say about the Lord Mahăvîra; but His life and work are shown in the philosophy

that He left, in that which He gave to the world, though the personality is

practically ignored.

Before him,

1,200 years, we are told, was the twenty-third of the Tirthamkaras, and then,

84,000 years before Him, the twenty-second and so on backwards and backwards in

the long scroll of time, until at last we come to the first of These,

Rishabhadeva, the father of King Bharata, who gave to India its name. There the

two faiths, Jainism and Hinduism, join, and the Hindu and the Jaina together

revere the Great One who, giving birth to a line of Kings, became the Rishi and

the teacher.

When we come to

look at the teaching from the outside — I will take the inside presently — we

find certain canonical Scriptures, as we call them, analogous to the Pitakas of

the Buddhists, forty-five in number; they are the Siddhănta, and they were

collected by Bhadrabăka, and reduced to writing, between the third and fourth

centuries before Christ. Before that, as was common in India, they were handed

down from mouth to mouth with that wonderful accuracy of memory which has ever

been characteristic of the transmission of Indian Scriptures. Three or four

hundred years before the reputed birth of Christ, they were put into writing, reduced,

the western world would say, to a fixed form. But we know well enough it was no

more fixed than in the faithful memories of the pupils who took them from the

Teacher; and even now as Max Müller tells us, if every Veda were lost they

could be textually reproduced by those who learn to repeat them. So the

Scriptures, the Siddhănta, remained written, collected by Bhadrabăka, at this

period before Christ. In A.D. 54 a council was held, the Council of Valabhi,

where a recension of these Scriptures was made, under Devard-digamin, the

Buddhaghosha of the Jainas. There are forty-five books, as I said; II Angas, 22

Upăngas, 10 Pakinnakas, 6 Chedas, 4 Műla-sűtras, and 2 other Sűtras. This makes

the canon of the Jaina religion, the authoritative Scripture of the faith.

There seem to have been older works than these, which have been entirely lost,

which are spoken of as the Pűrvas, but of these, it is said, nothing is known.

I do not think that that is necessarily true. The Jainas are peculiarly

secretive as to their sacred books, and there are masterpieces of literature,

among the sect of Digambaras, which are entirely withheld from publication; and

I shall not be surprised if in the years to come many of these books, which are

supposed to be entirely lost, should be brought out, when the Digambaras have

learnt that, save in special cases, it is well to spread abroad truths, that

men may have them. Secretiveness may be carried so far as to be a vice, beyond

the bounds of discretion, beyond the bounds of wisdom.

Then outside the

canonical Scriptures there is an enormous literature of Purănas and Itihăsas,

resembling very much the Purănas and Itihăsas of the Hindus. They are said, I

know not whether truly or not, to be more systematized than the Hindu versions;

what is clear is that in many of the stories there are variations, and it would

be an interesting task to compare these side by side, and to trace out these

variations, and to try and find the reasons that have caused them.

So much for what

we may call their special literature; but when we have run over that, we find

that we are still faced by a vast mass of books, which, although originating in

the Jaina community, have become the common property of all India — grammars,

lexicons, books on rhetoric and on medicine — these are to be found in immense

numbers and have been adopted wholesale in India. The well-known Amarakosha,

for instance, is a Jaina work that every student of Sanskrit learns from

beginning to end.

I said the

Jainas came to Southern India — spreading downwards through the whole of the

southern part of the peninsula; we find them giving kings to Madura, to

Trichinopoly and to many another city in Southern India. We find not only that

they thus give rulers; but we find they are the founders of Tamil literature.

The Tamil grammar, said to be the most scientific grammar that exists, is a

Jaina production. The popular grammar, Nămal, by Pavanandi, is Jaina, as

is Năladiyăr. The famous poet Tiruvalluvar's Kural, known I

suppose to every Southerner, is said to be a Jaina work, for this reason, that

the terms he uses are Jaina terms. He speaks of the Arhats; he uses the

technical terms of the Jaina religion, and so he is regarded as belonging to

the Jaina faith.

The same is true

of the Canarese literature; and it is said that from the first century of the

Christian Era to the twelfth, the whole literature of Canara is dominated by

the Jainas. So great then were they in those days.

Then there came

a great movement throughout Southern India, in which the followers of Mahădeva,

Siva, came preaching and singing through the country, appealing to that deep

emotion of the human heart, Bhakti, which the Jaina had too much ignored.

Singing stotras to Mahădeva they came, chanting His praises, especially working

cures of diseases in His name, and before these wonderful cures and the rush of

the devotion which was aroused by their singing and preaching, many of the

Jainas were themselves converted; the remainder of them were driven away, so

that in Southern India they became practically non-existent. Such is their

story in the South; such the fashion of their vanishing.

In Rajputana,

however, they remained, and so highly were they respected that Akbar, the

magnanimous Musalmăn emperor, issued an edict that no animals, should be killed

in the neighbourhood of Jaina temples.

The Jainas are

divided, we may add, into two great sects — the Digambaras, known in the fourth

century B.C., and mentioned in one of Asoka's edicts; the Svetambaras,

apparently more modern. The latter are now by far the more numerous, but it is

said that the Digambaras possess far vaster libraries of ancient literature

than does the rival sect.

Leave that

historical side; let us now turn to their philosophic teaching. They assert two

fundamental existences, the root, the origin, of all that is, of Samsăra; these

are uncreated, eternal. One is Jîva or Atma, pure consciousness, knowledge, the

Knower, and when the Jîva has transcended Avidyă, ignorance, then he realizes

himself as the pure knowledge that he is by nature, and is manifested as the

Knower of all that is. On the other hand Dravya, substance, that which is

knowable; the Knower and the Knowable opposed one to the other; Jîva and

Dravya. But Dravya is to be thought of as always connected with Guna, quality.

Familiar enough, of course, are all these ideas to you, but we must follow them

one by one. With Dravya is not only Guna, quality, but Paryăya, modification.

“ Substance is

the substrate of qualities; the qualities are inherent in one substance; but

the characteristic of developments is that they inhere in either.

“Dharma,

Adharma, space, time, matter and souls (are the six kinds of substances), they

make up this world, as has been taught by the Jinas who possess the best

knowledge.” [Uttaradhyayana, xxviii, 6, 7. Translated from the

Prakrit, by Hermann Jacobi]

Here you have

the basis of all Samsara; the Knower and the Knowable, Jîva and Dravya with its

qualities and its modifications. This makes up all. Out of these principles

many deductions, into which we have not the time to go; I may give you,

perhaps, one, taken from a Gătha of Kundăcărya, which will show you a line of

thought not unfamiliar to the Hindu. Of everything, they say, you can declare

that it is, that it is not, that it is and is not. I take their own example,

the familiar jar. If you think of the jar as Paryăya, modification, then before

that jar is produced, you will say: “Syănnăsti” it is not. But if you think of

it as substance, as Dravya, then it is always existing, and you will say of it:

“Syădasti”, it is; but you can say of it as Dravya and Paryăya, it is not

and it is, and sum up the whole of it in a single phrase: “Syădasti năsti”; it is and it

is not.[Report of the Search for Sanskrit MSS BY Dr Bhandarkar, p

95] Familiar line of reasoning enough. We can find dozens, scores and

hundreds of illustrations of this way of looking at the universe, wearisome,

perhaps, to the ordinary man, but illuminative and necessary to the

metaphysician and the philosopher.

Then we come to

the growth, or rather the unfolding, of the Jîva. The Jîva evolves, it is

taught, by Reincarnation and by Karma; still, as you see, we are on very

familiar ground. “The universe is peopled by manifold creatures who are in

this Samsăra, born in different families and castes for having done various

actions. Sometimes they go to the worlds of the Gods, sometimes to the hells,

sometimes they become Asuras, in accordance with their actions. Thus living

beings of sinful actions who are born again and again in ever-recurring births,

are not disgusted with Samsăra.” [Uttaradhyayana, iii, 2, 3,

5] And it teaches exactly as you read in the Bhagavad-Gîtă that

the human being goes downwards by evil action; by mixed good and evil he will

be born as a man; or, if purified, will be born as a Deva. Exactly on these

lines the Jaina teaches. It is by many births, by innumerable experiences, the

Jîva begins to liberate himself from the bonds of action. We are told that

there are three jewels, like the three ratnas that we so often hear of among

the Buddhists; and these are said to be right knowledge, right faith, right

conduct, a fourth being added for ascetics: “Learn the true road leading to

final deliverance, which the Jinas have taught; it depends on four causes, and

is characterized by right knowledge and faith. I. Right knowledge; II. Faith;

III. Conduct; IV. Austerities. This is the road taught by the Jinas who possess

the best knowledge.” [Ibid, xxviii, 1, 2]

By right knowledge and right faith and right conduct the Jîva evolves, and in

the later stages, to these are added austerities, by which he finally frees

himself from the bonds of rebirth. Right knowledge is defined as being that

which I have just said to you with regard to Samsăra; and the difference of Jîva

and Dravya, and the six kinds of substances, Dharma, Adharma, space, time,

matter, soul; he must also know the nine truths: Jiva, soul; Ajîva, the

inanimate things; Bandha, the binding of the soul by karma; Punya, merit; Păpa,

demerit; Âsrăva, that which causes the soul to be affected by sins; Samvara,

the prevention of Âsrăva by watchfulness; the annihilation of Karma; final

deliverance; these are the nine truths.[Uttaradhyayana, xxviii,

14]

Then we find a

definition as to right conduct. Right conduct, which is Sarăga, with desire,

leads to Svarga — or it leads to becoming a Deva, or it leads to the

sovereignty of the Devas, Asuras and men, but not to liberation. But the right

conduct which is Vîtarăga, free from desire, that, and that alone, will lead to

final liberation. As we still follow the course of the Jîva, we find him

throwing aside Moha, delusion, Răga, desire, Dvesha, hatred, and of course

their opposites, for the one cannot be thrown off without the other; until at

last he becomes the Jîva complete and perfect, purified from all evil,

omniscient, omnipotent and omnipresent, the whole universe reflected in himself

as in a mirror, pure consciousness, “with the powers of the senses, though

without the senses”; pure consciousness, the knower, the

Supreme.

Such then is a

brief outline of the views, the philosophic views, of the Jainas, acceptable

surely to every Hindu, for on almost every point you will find practically the

same idea, though put sometimes in a somewhat different form.

Let us look more

closely at right conduct, for here the Jaina practice becomes specially

interesting; and wise are many of his ways, in dealing especially with the life

of the layman. Jainas are divided into two great bodies: the layman, who is

called a Srăvaka, and the ascetic, the Yati. These have different rules of

conduct in this sense only, that the Yati carries to perfection that for which

the layman is only preparing himself in future births. The five vows of the

Yati which I will deal with in a moment, are also binding on the layman to a

limited extent. To take a single instance: the vow of Brahmacarya, that on the

Yati imposes of course absolute celibacy, in the layman means only temperance

and proper chastity in the life of a Grhastha. In this way the vows, we may

say, run side by side, of Ahimsa, harmlessness, Sűnriti, truthfulness, Asteya,

not taking that which is not one's own, uprightness, honesty, Brahmacarya, and

finally Aparigraha, not grasping at anything, absence of greed — in the case of

the layman meaning that he is not to be covetous, or full of desire; in the

case of the Yati meaning of course that he renounces everything and knows

nothing as “mine”, “my own”. These five

vows, then, rule the life of the Jaina. Very, very marked is his translation of

the word Ahimsa, harmlessness: “thou shalt not kill”. So far does

he carry it in his life, to such an extreme, that it passes sometimes almost

beyond the bounds of virtue; passes, a harsh critic might say, into absurdity;

but I am not willing so to say, but rather to see in it the protest against the

carelessness of animal life and animal suffering, which is but too widely

spread among men; a protest, I admit, carried to excess, all sense of

proportion being lost, the life of the insect, the gnat, sometimes being

treated as though it were higher than the life of a human being. But still,

perhaps, that may be pardoned, when we think of the extremes of the cruelty to

which so many permit themselves to go; and although a smile may sometimes come when

we hear of breathing only through a cloth, as the Yati does, as he breathes

continually touching the lips that nothing living may go into the lungs;

straining all water and most unscientifically boiling it — which really

“kills creatures, which if water remained unboiled would remain alive — the

smile will be a loving one, for the tenderness is beautiful. Listen for a

moment to what was said by a Jina, and would to God that all men would take it

as a rule of life: “The venerable One has declared ... As is my pain when I

am knocked or struck with a stick, bow, fist, clod, or potsherd; or menaced,

beaten, burned, tormented, or deprived of life; and as I feel every, pain and

agony, from death down to the pulling out of a hair; in the same way, be sure of

this, all kinds of beings feel the same pain and agony, etc., as I, when living

they are ill-treated in the same way. For this reason all sorts of living

beings should not be beaten, nor treated with violence, nor abused, nor

tormented, nor deprived of life. I say the Arhats and Bhagavats of the past,

present and future, all say thus, speak thus, declare thus, explain thus; all

sorts of living beings should not be slain, nor treated with violence, nor

abused, nor tormented, nor driven away. This constant, permanent, eternal, true

law has been taught by wise men who comprehend all things.” [Uttaradhyayana,

Bk II, i, 48, 49]

If that were the

rule for every one, how different would India be; no beaten and abused animal;

no struggling, suffering creature; and for my part, I can look almost with

sympathy even on the Jaina exaggeration, that has a basis so noble, so

compassionate; and I would that the feeling of love, though not the

exaggeration, should rule in all Indian hearts of every faith today.

Then we have the

strict rule that no intoxicating; drug or drink may be touched; nothing like

bhang, opium, alcohol; of course nothing of this kind is allowed; even so far

as honey and butter does the law of forbidden food go, because in the gaining

of honey the lives of bees are too often sacrificed, and so on. Then we find in

the daily life of the Jaina rules laid down for the layman as to how he is to

begin and end every day:

“He must rise

very very early in the morning and then he must repeat silently his mantras,

counting its repetition on his fingers; and then he has to say to himself, what

am I, who is my Ishtadeva, who is my Gurudeva, what is my religion, what should

I do, what should I not do? ” This is the beginning of each day, the

reckoning up of life as it were; careful, self-conscious recognition of life.

Then he is to think of the Tirthamkaras, and then he is to make certain vows.

Now these vows are peculiar, as far as I know, peculiar to the Jainas,

and they have an object which is praiseworthy and most useful. A man at his own

discretion makes some small vow on a thing absolutely unimportant. He will say

in the morning: “During this day” — I will take an extreme case given to me

by a Jaina — “during this day I will not sit down more than a certain number

of times”; or he will say: “For a week I will not eat such and such a

vegetable”; or he will say: “For a week, or ten days, or a month, I will

keep an hour's silence during the day”. You may say: Why? In order that the man

may always be self-conscious, and never lose his control over the body. That is

the reason that was given me by my Jaina friend, and I thought it an extremely

sensible one. From young boyhood a boy is taught to make such promises, and the

result is that it checks thoughtlessness, it checks excitement, it checks that

continual carelessness, which is one of the great banes of human life. A boy

thus educated is not careless. He always thinks before he speaks or acts; his

body is taught to follow the mind and not to go before the mind, as it does too

often. How often do people say: “ If I had thought, I would not have done it;

if I had considered, I would never have acted thus; if I had thought for a

moment that foolish word would not have been spoken, and that harsh speech

would never have been uttered, that discourteous action would never have been

done.” If you train yourself from childhood never to speak without

thinking, never to act without thinking, see how unconsciously the body would learn

to follow the mind, and without struggle and effort, carelessness would be

destroyed. Of course there are far more serious vows than these taken by the

layman as to fasting, strict and severe, every detail carefully laid down in

the rules, in the books. But I was telling you a point that you would not so

readily find in the books, so far as I know and that seemed to me to be

characteristic and useful. Let me add that when you meet Jainas you will find

them, as a rule, what you might expect from this training — quiet,

self-controlled, dignified, rather silent, rather reserved. [The details

here given are mostly from the Jainatattvădarsha, by Muni Atmărămji, and

were translated from the Prakrit for me by my friend Govinda Dasa]

Pass from the

layman to the ascetic, the Yati. Their rules are very strict. Much of fasting,

carried to an extraordinary extent, just like the fasting of the great ascetics

of the Hindu. There are both men and women ascetics among the sect known as the

Svetămbaras; among the Digambaras there are no female ascetics and their views

of women are perhaps not on the whole very complimentary. Among the

Svetămbaras, however, there are female ascetics as well as male, under the same

strict rules of begging, of renouncing of property; but one very wise rule is

that the ascetic must not renounce things without which progress cannot be

made. Therefore he must not renounce the body; he must beg food enough to

support it, because only in the human body can he gain liberation. He must not

renounce the Guru, because without the teaching of the Guru he cannot tread the

narrow razor path; nor discipline, for if he renounces that, progress would be

impossible; nor the study of the Sűtras, for that also is needed for his

evolution; but outside these four things — the body, the Guru, discipline,

study — there must be nothing of which he can say: “it is mine”. Says a

teacher: “He should not speak unasked, and asked he should not tell a lie; he

should not give way to his anger, and should bear with indifference, pleasant

and unpleasant occurrences. Subdue your self, for the self is difficult to

subdue; if your self is subdued, you will be happy in this world and in the

next.”[Uttaradhyayana,

i, 14, 15]

The female

ascetics, living under the same strict rule of conduct, have one duty which it

seems to me is of the very wisest provision; it is the duty of female ascetics

to visit all the Jaina households, and to see that the Jaina women, the wives

and the daughters, are properly educated, properly instructed. They lay great

stress on the education of the women, and one great work of the female ascetic

is to give that education and to see that it is carried out. There is a point

that I think the Hindu might well borrow from the Jaina, so that the Hindu women

might be taught without the chance of losing their ancestral faith, or

suffering interference with their own religion, taught by ascetics of their own

creed. Surely no vocation can be nobler, surely it would be an advantage to

Hinduism.

And then how is

the ascetic to die? By starvation. He is not to wait until death touches him;

but when he has reached that point where in that body he can make no further

progress, when he has reached that limit of the body, he is to put it aside and

pass out of the world by death by voluntary starvation.

Such is a brief

and most imperfect account of a noble religion, of a great faith which is

practically, we may say, on almost all points, at one with the Hindu; and so

much is this the case that in Northern India the Jaina and the Hindu Vaishyas

intermarry and interdine. They do not regard themselves as of different

religions, and in the Hindu college we have Jaina students, Jaina boarders, who

live with their Hindu brothers, and are thus from the time of childhood helping

to draw closer and closer together the bonds of love and of brotherhood. I

spoke to you yesterday about nation-building, and reminded you that here in

India we must build our nation out of the men of many faiths. With Jainas no

difficulty can well arise, save by the bigotry that we find alike among the

less instructed of every creed, which it is the duty of the wiser, the more

thoughtful, the more religious, the more spiritual, to gradually lessen. Let

every man in his own faith teach the ignorant to love and not to hate. Let him

lay stress on the points that unite us, and not on the points that separate us.

Let every man in his daily life speak never a word of harshness for any faith,

but words of love to all. For in thus doing we are not only serving God, but

also serving man; we are not only serving religion, we are also serving India,

the common Motherland of all; all are Indians, all are children of India, all

must have their places in the Indian nation of the future. Then let us, any

brothers, strive to do our part in the building, if it be but by bringing one

small brick of love to the mighty edifice of Brotherhood; and let no man who

takes the name of a Theosophist, a lover of the Divine Wisdom, ever dare to say

one word of harshness as regards one faith that God has given to man, for they

all come from Him, to Him they all return, and what have we to do with

quarrelling by the way?

History

of the Theosophical Society

Theosophical Society Cardiff

Lodge

Cardiff Theosophical Archive

The Theosophical Society, Cardiff

Lodge, 206 Newport Road, Cardiff CF24 – 1DL

For more info on Theosophy

Try these

Dave’s Streetwise Theosophy

Boards

Cardiff

Lodge’s Instant Guide to Theosophy

One

Liners & Quick Explanations

The

Most Basic Theosophy Website in the Universe

If you run a Theosophy Group

you can use

this as an introductory

handout

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky 1831 – 1891

The Founder of Modern Theosophy

Index of Articles by

By

H P Blavatsky

Is the Desire to Live Selfish?

Ancient Magic in Modern Science

Precepts Compiled by H P Blavatsky

Obras Por H P Blavatsky

En Espanol

Articles about the Life of H P Blavatsky

Try these if you are

looking for a local group

UK Listing of

Theosophical Groups

Worldwide

Directory of Theosophical Links

Nature is infinite in space and

time -- boundless and eternal, unfathomable and ineffable. The all-pervading

essence of infinite nature can be called space, consciousness, life, substance,

force, energy, divinity -- all of which are fundamentally one.

2) The finite and the infinite

Nature is a unity in

diversity, one in essence, manifold in form. The infinite whole is composed of

an infinite number of finite wholes -- the relatively stable and autonomous

things (natural systems or artefacts) that we observe around us. Every natural

system is not only a conscious, living, substantial entity, but is

consciousness-life-substance, of a particular range of density and form.

Infinite nature is an abstraction, not an entity; it therefore does not act or

change and has no attributes. The finite, concrete systems of which it is

composed, on the other hand, move and change, act and interact, and possess

attributes. They are composite, inhomogeneous, and ultimately transient.

3)

Vibration/worlds within worlds

The one essence manifests not

only in infinitely varied forms, and on infinitely varied scales, but also in

infinitely varying degrees of spirituality and substantiality, comprising an

infinite spectrum of vibration or density. There is therefore an endless series

of interpenetrating, interacting worlds within worlds, systems within systems.

The energy-substances of

higher planes or subplanes (a plane being a particular range of vibration) are

relatively more homogeneous and less differentiated than those of lower planes

or subplanes.

Just as boundless space is

comprised of endless finite units of space, so eternal duration is comprised of

endless finite units of time. Space is the infinite totality of worlds within

worlds, but appears predominantly empty because only a tiny fraction of the

energy-substances composing it are perceptible and tangible to an entity at any

particular moment. Time is a concept we use to quantify the rate at which

events occur; it is a function of

change and motion, and

presupposes a succession of cause and effect. Every entity is extended in space

and changes 'in time'.

All change (of position,

substance, or form) is the result of causes; there is no such thing as absolute

chance. Nothing can happen for no reason at all for nothing exists in

isolation; everything is part of an intricate web of causal interconnections and

interactions. The keynote of nature is harmony: every action is automatically

followed by an equal and opposite reaction, which sooner or later rebounds upon

the originator of the initial act. Thus, all our thoughts and deeds will

eventually bring us 'fortune' or 'misfortune' according to the degree to which

they were harmonious or disharmonious. In the long term, perfect justice

prevails in nature.

Because nature is

fundamentally one, and the same basic habits and structural, geometric, and

evolutionary principles apply throughout, there are correspondences between

microcosm and macrocosm. The principle of analogy -- as above, so below -- is a

vital tool in our efforts to understand reality.

All finite systems and their

attributes are relative. For any entity, energy-substances vibrating within the

same range of frequencies as its outer body are 'physical' matter, and finer

grades of substance are what we call energy, force, thought, desire, mind,

spirit, consciousness, but these are just as material to entities on the

corresponding planes as our physical world is to us. Distance and time units

are also relative: an atom is a solar system on its own scale, reembodying perhaps

millions of times in what for us is one second, and our whole galaxy may be a

molecule in some supercosmic entity, for which a million of our years is just a

second. The range of scale is infinite: matter-consciousness is both infinitely

divisible and infinitely aggregative.

All natural systems consist

of smaller systems and form part of larger systems. Hierarchies extend both

'horizontally' (on the same plane) and 'vertically' or inwardly (to higher and

lower planes). On the horizontal level, subatomic particles form atoms, which

combine into molecules, which arrange themselves into cells, which form tissues

and organs, which form part of organisms, which form part of ecosystems, which

form part of planets, solar systems, galaxies, etc. The constitution of worlds

and of the organisms that inhabit them form 'vertical' hierarchies, and can be

divided into several interpenetrating layers or elements, from physical-astral

to psychomental to spiritual-divine, each of which can be further divided.

The human constitution can be

divided up in several different ways: e.g. into a trinity of body, soul, and

spirit; or into 7 'principles' -- a lower quaternary consisting of physical

body, astral model-body, life-energy, and lower thoughts and desires, and an

upper triad consisting of higher mind (reincarnating ego), spiritual intuition,

and inner god. A planet or star can be regarded as a 'chain' of 12 globes, existing

on 7 planes, each globe comprising several subplanes.

The highest part of every

multilevelled organism or hierarchy is its spiritual summit or 'absolute',

meaning a collective entity or 'deity' which is relatively perfected in

relation to the hierarchy in question. But the most 'spiritual' pole of one

hierarchy is the most 'material' pole of the next, superior hierarchy, just as

the lowest pole of one hierarchy is the highest pole of the one below.

Each level of a hierarchical

system exercises a formative and organizing influence on the lower levels

(through the patterns and prototypes stored up from past cycles of activity),

while the lower levels in turn react upon the higher. A system is therefore

formed and organized mainly from within outwards, from the inner levels of its

constitution, which are relatively more enduring and developed than the outer

levels. This inner guidance is sometimes active and selfconscious, as in our

acts of free will (constrained, however, by karmic tendencies from the past),

and sometimes it is automatic and passive, giving rise to our own automatic

bodily functions and habitual and instinctual behavior, and to the orderly,

lawlike operations of nature in general. The 'laws' of nature are therefore the

habits of the various grades of conscious entities that compose reality,

ranging from higher intelligences (collectively

forming the universal mind) to elemental nature-forces.

10) Consciousness and its vehicles

The core of every entity --

whether atom, human, planet, or star -- is a monad, a unit of consciousness-life-substance,

which acts through a series of more material vehicles or bodies. The monad or

self in which the consciousness of a particular organism is focused is animated

by higher monads and expresses itself through a series of lesser monads, each

of which is the nucleus of one of the lower vehicles of the entity in question.

The following monads can be distinguished: the divine or galactic monad, the

spiritual or solar monad, the higher human or planetary-chain monad, the lower

human or globe monad, and the animal, vital-astral, and physical monads. At our

present stage of evolution, we are essentially the lower human monad, and our

task is to raise our consciousness from the animal-human to the spiritual-human

level of it.

Evolution means the

unfolding, the bringing into active manifestation, of latent powers and

faculties 'involved' in a previous cycle of evolution. It is the building of

ever fitter vehicles for the expression of the mental and spiritual powers of

the monad. The more sophisticated the lower vehicles of an entity, the greater

their ability to express the powers locked up in the higher levels of its

constitution. Thus all things are alive and conscious, but the degree of

manifest life and consciousness is extremely varied.

Evolution results from the

interplay of inner impulses and environmental stimuli. Ever building on and

modifying the patterns of the past, nature is infinitely creative.

12) Cyclic evolution/re-embodiment

Cyclic evolution is a

fundamental habit of nature. A period of evolutionary activity is followed by a

period of rest. All natural systems evolve through re-embodiment. Entities are

born from a seed or nucleus remaining from the previous evolutionary cycle of

the monad, develop to maturity, grow old, and pass away, only to re-embody in a

new form after a period of rest. Each new embodiment is the product of past

karma and present choices.

Nothing comes from nothing:

matter and energy can be neither created nor destroyed, but only transformed.

Everything evolves from preexisting material. The growth of the body of an

organism is initiated on inner planes, and involves the transformation of higher

energy-substances into lower, more material ones, together with the attraction

of matter from the environment.

When an organism has

exhausted the store of vital energy with which it is born, the coordinating

force of the indwelling monad is withdrawn, and the organism 'dies', i.e. falls

apart as a unit, and its constituent components go their separate ways. The

lower vehicles decompose on their respective subplanes, while, in the case of

humans, the reincarnating ego enters a dreamlike state of rest and assimilates

the experiences of the previous incarnation. When the time comes for the next

embodiment, the reincarnating ego clothes itself in many of the same atoms of

different grades that it had used previously, bearing the appropriate karmic

impress. The same basic processes of birth, death,

and rebirth apply to all entities, from atoms to humans to stars.

14)

Evolution and involution of worlds

Worlds or spheres, such as

planets and stars, are composed of, and provide the field for the evolution of,

10 kingdoms -- 3 elemental kingdoms, mineral, plant, animal, and human

kingdoms, and 3 spiritual kingdoms. The impulse for a new manifestation of a

world issues from its spiritual summit or hierarch, from which emanate a series

of steadily denser globes or planes; the One expands into the many. During the

first half of the evolutionary cycle (the arc of descent) the energy-substances

of each plane materialize or condense, while during the second half (the arc of

ascent) the trend is towards dematerialization or etherealization, as globes

and entities are reabsorbed into the spiritual hierarch for a period of nirvanic

rest. The descending arc is characterized by the evolution of matter and

involution of spirit, while the ascending arc is characterized by the evolution

of spirit and involution of matter.

In each grand cycle of

evolution, comprising many planetary embodiments, a monad begins as an

unselfconsciousness god-spark, embodies in every kingdom of nature for the

purpose of gaining experience and unfolding its inherent faculties, and ends

the cycle as a self conscious god. Elementals ('baby monads') have no free

choice, but automatically act in harmony with one another and the rest of

nature. In each successive kingdom differentiation and individuality increase,

and reach their peak in the human kingdom with the attainment of

selfconsciousness and a large measure of free will.

In the human kingdom in

particular, self-directed evolution comes into its own. There is no superior

power granting privileges or handing out favours; we evolve according to our

karmic merits and demerits. As we progress through the spiritual kingdoms we

become increasingly at one again with nature, and willingly 'sacrifice' our

circumscribed selfconscious freedoms (especially the freedom to 'do our own

thing') in order to work in peace and harmony with the greater whole of which

we form an integral part. The highest gods of one hierarchy or world-system

begin as elementals in the next. The matter of any plane is composed of

aggregated, crystallized monads in their nirvanic sleep, and the spiritual and

divine entities embodied as planets and stars are the electrons and atomic

nuclei -- the material building blocks -- of worlds on even larger scales.

Evolution is without beginning and without end, an endless adventure through

the fields of infinitude, in which there are always new worlds of experience in

which to become selfconscious masters of life.

There is no absolute

separateness in nature. All things are made of the same essence, have the same

spiritual-divine potential, and are interlinked by magnetic ties of sympathy.

It is impossible to realize our full potential, unless we recognize the

spiritual unity of all living beings and make universal brotherhood the keynote

of our lives.

Hey Look! Theosophy in

Cardiff

Cardiff Theosophical Society

in Wales

Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 – 1DL

_________________

Wales Picture Gallery

The

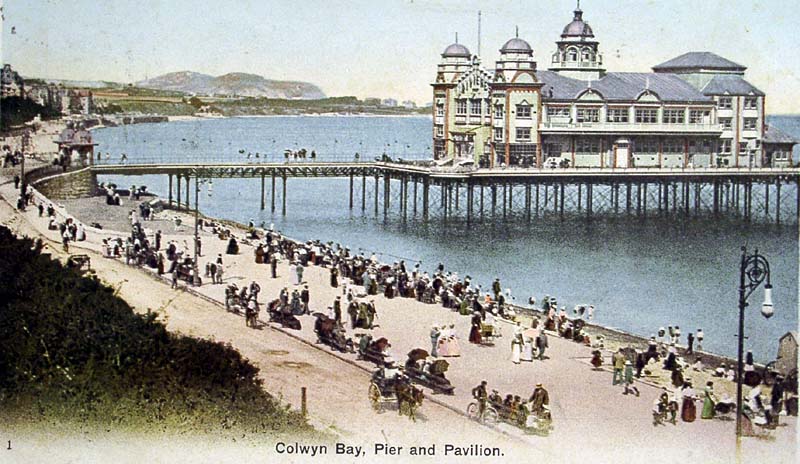

Great Orme

Llandudno

Promenade

Great

Orme Tramway

New

Radnor

Blaenavon

Ironworks

Llandrindod

Wells

Cardiff Theosophical Society

in Wales

Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 – 1DL

Presteign

Railway

Caerwent Roman Ruins

Denbigh

Nefyn

Penisarwaen

Cardiff Theosophical Society

in Wales

Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 – 1DL