The Theosophical Society,

Memories Of Past Lives

By

Annie Besant (1847 - 1933)

First published in 1932

Annie

Besant was active in Theosophical circles and a collaborator with

Archbishop

C. W. Leadbeater.

THERE

is probably no man now living in the scientific world who does not regard the

theory of physical evolution as beyond dispute; there may be many varieties of

opinion with regard to details and methods of evolution, but on the fundamental

fact, that forms have proceeded from the homogeneous to the heterogeneous,

there is complete harmony of educated opinion. Moreover, the evolutionary idea

dominates all departments of thought, and is applied to society as much as to

the individual. In history it is used as the master-key wherewith to unlock the

problems of the growth of nations, and, in sociology, of the progress of

civilisations. The rise, the decay, the fall of races are illuminated by this

all-pervading idea, and it is difficult now for anyone to throw himself in

thought back into the time when law gave way to miracle, and order was replaced

by fortuitous irregularity.

In

working up to the hypothesis of evolution small indications were searched

for,

as much as long successions were observed. Things apparently trifling were

placed

on record, and phenomena apparently trivial were noted with meticulous

care.

Above all, any incident which seemed to conflict with a recognised law of

nature

was minutely observed and repeatedly scrutinised, since it might be the

indication

of some force as yet undiscovered, of some hidden law working along lines as

yet unknown. Every fact was observed and recorded, challenged and discussed,

and each contributed something to the great pyramid of reasons which pointed to

evolution as the best hypothesis for explanation of the phenomena of nature.

Your dog turned round and round on the hearthrug before composing himself to sleep

; was he not governed by an unconscious memory from the times when his

ancestors thus prepared a comfortable depression in the jungle for their

repose? Your cat pressed her fore-paws on the ground, pushing outwards

repeatedly; was it not an unconscious memory which dominated her from the need

of her larger predecessors encircled by the tall grass of the forest

hiding-place,

to flatten out a sufficient bed for luxurious rest? Slight, in

truth,

are such indications, and yet withal they make up, in their accumulation,

a

massive argument in favour of unconscious memories of past lives being wrought

into the very fabric of the animal body.

But

there is one line of questions, provocative of thought, that has not yet

been

pursued with industry equal to that bestowed on the investigation of bodily

movements

and habits. The questions remain unanswered, either by biologist or

psychologist.

Evolution has traced for us the gradual building of our now

complex

and highly organised bodies; it has shown them to us evolving, in the

long

course of millions of years, from a fragment of protoplasm, from a simple

cell,

through form after form, until their present condition has been reached,

thus

demonstrating a continuity of forms, advancing into greater perfection as

organisms!

But so far science has not traced a correlative continuity of

consciousness

- a golden thread on which the innumerable separated bodies might be threaded

a consciousness inhabiting and functioning through this succession of forms. It

has not been able to prove nay, it has not even recognised' the likelihood of

the possibility - that consciousness passes on unbroken from body to body,

carrying with it an ever-increasing content, the accumulated harvest of

innumerable experiences, transmuted into capacities, into powers.

Scientists

have directed our attention to the splendid inheritance that has come

down

to us from the past. They have shown us how generation after generation has contributed

something to the sum of human knowledge, and how cycle after cycle manifests a

growth of average humanity in intellectual power, in extent of

consciousness,

in fineness and beauty of emotion. But if we ask them to explain

the

conditions of this growth, to describe the passing on of the content of one

consciousness

to another ; if we ask for some method, comparable to the methods observed in

the physical world, whereby we may trace this transmission of the treasures of

consciousness, may explain how it made its habits and accumulates experiences

which it transforms into mental and moral capacities, then science returns us

no answers, but fails to show us the means and the methods of the evolution of

consciousness in man.

When,

in dealing with animals, science points to the so-called inherited instincts,

it does not offer any explanation of the means whereby an intangible

self-preserving instinct can be transmitted by an animal to its offspring. That

there is some purposive and effective action, apart from any possibility of

physical experience having been gained as its instigator, performed by the

young of an animal, we can observe over and over again. Of the fact there can

be no question. The young of animals, immediately after coming into the world,

are

seen

to play some trick whereby they save themselves from some threatening

danger.

But science does not tell us how this intangible consciousness of danger

can

be transmitted by the parent, who has not experienced it, to the offspring

who

has never known it. If the life-preserving instinct is transmissible through

the

physical body of the parent, how did the parent come to possess it ? If the

chicken

just out of the shell runs for protection to the mother-hen when the

shadow

of a hawk hovering above it is seen, science tells us that it is prompted

by

the life-preserving instinct, the result of the experience of the danger of

the

hovering hawk, so many having thus perished that the seeking of protection

from

the bird of prey is transmitted as an instinct. But the difficulty of

accepting

this explanation lies in the fact that the experience necessary to

evolve

the instinct can only have been gained by the cocks and hens who were

killed

by birds of prey; these had no chance thereafter of producing eggs, and

so

could not transmit their valuable experience, while all the chicks come from

eggs

belonging to parents who had not experienced the danger, and hence could

not

have developed the instinct. (I am assuming that the result of such

experiences

in transmissible as an instinct an assumption which is quite

unwarranted.)

The only way of making the experiences of slaughtered animals

reappear

later as a life-preserving instinct is for the record of the experience

to

be preserved by some means, and transmitted as an instinct to those belonging

to the same type.

The

Theosophist points to the existence of matter finer than the physical, which

vibrates in correspondence with any mood of consciousness in this case the

shock of sudden death. That vibration tends to repeat itself, and that tendency

remains, and is reinforced by similar experiences of other slaughtered poultry;

this, recorded in the "group-soul", passes as a tendency into all the

poultry race, and shows itself in the newly hatched chick the moment the danger

threatens the new form. Instinct is " unconscious memory",

"inherited experience", but, each one who possesses it takes it from

a continuing consciousness, from which his separate lower consciousness is derived.

How else can it have originated, how else have been transmitted ?

Can

it be said that animals learn of danger by the observation of others who

perish

? That would not explain the unconscious memory in our newly-hatched

chicken,

who can have observed nothing. But apart from this, it is clear that

animals

are curiously slow either to observe, or to learn the application to

themselves

of the actions, the perils, of others.

How

often do we see a motherly hen running along the side of a pond, clucking

desperately to her brood of ducklings that have plunged into the water to the

manifest discomposure of the non-swimming hen; but she does the same thing

brood after brood; she never learns that the ducklings are able to swim and that

there is no danger to be apprehended when they plunge into the water. She calls

them as vigorously after ten years of experience as she did after the first

brood, so that it does not look as if instinct originated in careful

observation of petty movements by animals who then transmit the results of

their observations to their offspring.

The

whole question of the continuity of consciousness a continuity necessary

to

explain the evolution of instinct as much as that of intelligence is

insoluble

by science, but has been readily solved by religion. All the great

religions

of the past and present have realised the eternity of the Spirit: "

God,"

it is written in a Hebrew Scripture, " created man to be the image of His

own

Eternity", and in that eternal nature of the Spirit lies the explanation

alike of instinct and of intelligence. In the intellect-aspect of this Spirit

all the harvests of the experiences of successive lives are stored, and from

the treasures of the spiritual memory are sent down assimilated experiences,

appearing as instincts, as unconscious memories of past lives, in the new-born

form. Every improved form receives as instincts and as innate ideas this wealth

of reminiscence: every intellectual and moral faculty is a store of reminiscences,

and education is but the awakening of memory.

Thus

religion illuminate that which science leaves obscure, and gives us a

rational,

an intelligible theory of the growth of instinct and of intellect; it

shows

us a continuity of a consciousness ever increasing in content, embodying

itself

in forms ever increasing in complexity. The view . that man consists not

only

of bodies in which the working of the law of heredity may be traced, but

also

is a living consciousness, growing, unfolding, evolving, by the

assimilation

of the food of experience this theory is an inevitable pendant to

the

theory of physical evolution, for the latter remains unintelligible without

the

former. Special creation, rejected from the physical world, cannot much

longer

be accepted in the psychical, nor be held to explain satisfactorily the

differences

between the genius and the dolt, between the congenital saint and

the

congenital criminal. Unvarying law, the knowledge of which is making man the

master of the physical world, must be recognised as prevailing equally in the

psychical.

The improving bodies must be recognised as instruments to be used for the

gaining of further experiences by the ever-unfolding consciousness.

A

definite opinion on this, matter can only be gained by personal study,

investigation

and research. Knowledge of the great truths of nature is not a

gift,

but a prize to be won by merit. Every human being must form his own

opinions

by his own strenuous efforts to discover truth, by the exercise of his

own

reasoning faculties, by the experiences of his own consciousness. Writers

who

garb their readers in second-hand opinions, as a dealer in second-hand

clothes

dresses his customers, will never turn out a decently costumed set of

thinkers;

they will be clad in misfits. But there are lines of research to be

followed,

experiences to be gone through and analysed, by those who would arrive at truth

research which has led others to knowledge, experiences which have been found

fruitful in results. To these a writer may point his readers, and

they,

if they will, may follow along such lines for themselves.

I

think we may find in our consciousness in our intelligence and our

emotional

nature distinct traces from the past which point to the evolution of our

consciousness, as the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the embryonic reptilian

heart

point to the ancestral line of evolution of our body. I think there are

memories

forming part of our consciousness which justify belief in previous

existences,

and point the way to a more intelligent understanding of human life.

I

think that, by careful observation, we may find memories in ourselves, not

only

of past events, but of the past training and discipline which have made us

what

we are, memories which are embedded in, which form even the very fabric of our

consciousness, which emerge more clearly as we study them, and become more

intelligible the more carefully we observe and analyse them.

But

for a moment we must pause on the theory of Reincarnation, on the broad

principle

of consciousness in evolution.

This

theory posits a Spirit, a seed or germ of consciousness planted in matter,

and

ultimately, after long ages of growth, becoming ready to enter an

undeveloped

human body, connected by its material with three worlds, the worlds of mind, of

desire and of action, otherwise called the heavenly, intermediate and physical

worlds. In the physical world this growing Spirit gathers experiences of varied

kinds, feels pleasures and pains, joys and sorrows, health and illness,

successes and disappointments, the many changing conditions which make up our

mortal life. He carries these on with him through death, and in the

intermediate world experiences the inevitable results of desires which clashed

with the laws of nature, reaping in suffering the harvest of his blundering

ignorance.

Thus

he shapes the beginnings of a conscience, the recognition of an external law of

conduct. Passing on to the heavenly world, be builds his mental

experiences

into mental faculties until, all the food of experience being

assimilated,

he begins again to hunger, and so returns to earth with the elements of a character,

still enveloped in many-folded ignorance, but starting with a little more

content of consciousness than he had in his previous life.

Such

is his cycle of growth, the passing through the three worlds over and over

again,

ever accumulating experience, ever transmuting it into power. That cycle

is

repeated over and over again, until the savage grows into the average man of

our

time, from the average man, to the man of talent, of noble character; then

onwards

to the genius, to the saint, to the hero; onwards still to the Perfect

Man;

onwards yet, through ever-increasing, unimaginable splendours, vanishing

into

blinding radiance which veils his further progress from our dazzled eyes.

Thus

every man builds himself, shapes his own destiny, is verily self-created ;

no

one of us is what we are save as we have wrought out our own being ; our

future

is not imposed on us by an arbitrary will or a soulless necessity, but is

ours

to fashion, to create. There is nothing we cannot accomplish if we are

given

time, and time is endless. We, the living consciousnesses, we pass from

body

to body, and each new body takes the impress made upon it by its tenant,

the

ever-young and immortal Spirit.

I

have spoken of the three stages of the life-cycle, each belonging to a

definite

world; it must be noted that in the physical stage of the life-period,

we

are living in all the three worlds, for we are thinking and desiring as well

as

acting, and our body, the vehicle of consciousness, is triple. We lose the

physical

part of the body at death, and the desire-part at a later period, and

live

in the mental body in which all good thoughts and pure emotions have

their

habitat while in the heavenly world. When the heaven life is over, the

mental

body also disintegrates, and there remains but the spiritual body whereof

S.

Paul speaks, "eternal in the heavens".. Into that, the lasting

clothing of

the

Spirit, are woven all the pure results of experiences gathered in the lower

worlds.

In the building of the new triple body for the new life-cycle in the

lower

worlds, a new apparatus comes into existence for the use of the spiritual

consciousness

and the spiritual body; and the latter, retaining within itself

the

conscious memory of past events, imprints on the lower its instruments for

gathering fresh experience only the results of the past, as faculties, mental

and

emotional, with many traces of past experiences which have been outgrown and

remain normally in the sub-consciousness. The conscious memory of past events

being present only in the spiritual body, the consciousness must be functioning

in that in order to "remember"; and such functioning is possible

through a system of training and discipline yoga which may be studied by

anyone who has perseverance, and a certain amount of innate ability for this

special kind of work.

But

in addition to this there are many unconscious memories, manifesting in

faculty,

in emotion, in power, traces of the past imprinted on the present, and

discoverable

by observations on our-selves and others. Hence, memories of the

past

may be clear and definite, obtained by the practice of yoga, or unconscious

but

shown by results, and closely allied in many ways to what are called

instincts,

by which you do certain things, think along certain lines, exercise

certain

functions, and possess certain knowledge without having consciously

acquired

it. Among the Greeks, and the ancients generally, much stress was laid

upon

this form of memory. Plato's phrase: "All knowledge is reminiscence",

will

be

remembered. In the researches of psychology today, many surges of feeling,

driving

a man to hasty, unpremeditated action, are ascribed to the

sub-consciousness,

i.e., the consciousness which shows itself in involuntary

thoughts,

feelings and actions; these come to us out of the far-off past,

without

our volition or our conscious creation. How do these come, unless there

be

continuity of consciousness ?

Any

who study modern psychology will see how great a part unconscious memory plays

in our lives, how it is said to be stronger than our reason, how it conjures up

pathetic scenes uncalled-for, how at night it throws us into causeless panics.

These, we are told, are due to memories of dangers surrounding savages, who

must ever be on the alert to guard themselves against sudden attacks, whether

of man or beast, breaking into the hours of repose, killing the men and women

as they slept. These past experiences are said to have left records in

consciousness, records which lie below the threshold of waking consciousness

but are ever present within us. And some say that this is the most important

part of our consciousness, though out of sight for the ordinary mind.

We

cannot deny to these the name of memory, these experiences out of the past

that

assert themselves in the present. Study these traces, and see whether they

are

explicable save by the continuity of consciousness, making the Self of the

savage

the Self which is yourself today, seeing the persistence of the

Individual

throughout human evolution, growing, expanding, developing, but a

fragment

of the eternal "I am".

May

we not regard instincts as memories buried in the sub-conscious, influencing

our actions, determining our "choices" ? Is not the moral instinct

Conscience, a mass of interwoven memories of past experiences, speaking with

the authoritative utterance of all instincts, and deciding on "

right" and " wrong " without argument, without reasoning? It

speaks clearly when we are walking on

well-trodden

ways, warning us of dangers experienced in the past, and we shun

them

at sight as the chicken shuns the down rush of the hawk hovering above it.

But

as that same chicken has no instinct as regards the rush of a motor-car, so

have

we no "voice of Conscience" to warn us of the pitfalls in ways

hitherto

unknown.

Again,

innate faculty what is it but an unconscious memory of subjects

mastered

in the past ? A subject, literary, scientific, artistic, what we will,

is

taken up by one person and mastered with extraordinary ease; he seizes at

sight

the main points in the study, taking it up as new, apparently, but so

rapidly

grasping it that it is obviously an old subject remembered, not a new

subject

mastered. A second person, by no means intellectually inferior, is

observed

to be quite dense along this particular line of study ; reads a book on

it,

but keeps little trace of it in his mind; addresses himself to its

understanding,

but it evades his grasp. He stumbles along feebly, where the

other

ran unshackled and at ease. To what can such difference be due save to the

unconscious memory which science is beginning to recognise ? One student has

known the subject and is merely remembering it; the other takes it up for the

first

time, and finds it difficult and obscure.

As

an example, we may take H. P. Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine, a difficult book;

it

is said to be obscure, diffuse, the style to be often unattractive, the

matter

very difficult to follow. I have known some of my friends take up these

volumes

and study them year after year, men and women, intelligent, quite alert

in

mind ; yet after years of study they cannot grasp its main points nor very

often

follow its obscure arguments. Let me put against that my own experience of that

book. I had not read anything of the subject with which it deals from the

standpoint

of the Theosophist; it was the first Theosophical book I had read

except

The Occult World and it came into my hands, apparently by chance, given to me

to review by Mr. Stead, then Editor of the Pall Mall Gazette. When I began to

read that book, I read it right through day after day, and the whole of it

was

so familiar as I read, that I sat down and wrote a review which anyone may

read

in the Pall Mall Gazette of, I think, February or March, 1889; and anyone

who

reads that review will find that I had taken the heart out of the book and

presented

it intelligently to the ordinary newspaper reader. That certainly was

not

from any special genius on my part.

If

I had been given a book of some other kind, I might have stumbled over it and

made nothing of it at all; but as I read I remembered, and the whole philosophy

fell into order before me, although to this brain and in this body it came

before me for the first time. I allege that in cases like that we have a proof

of the accuracy of Plato's idea, mentioned already, that all knowledge is

reminiscence; where we have known before we do really remember, and so master

without any effort that which another, without a similar experience, may find

abstruse, difficult and obscure.

We

may apply this to any new subject that anyone may take up. If he has learned it

before, he will remember and master the subject easily; if not, taken as a new

thing, he must learn step by step, and gradually understand the relation

between the phenomena studied, working it out laboriously because unknown.

Let

us now apply that same idea of memory to genius, say to musical genius. How can

we explain, except by previous knowledge existing as memory, the mystery of a

little child who sits down to a piano and with little teaching, or with none,

outstrips many who have given years of labour to the art ? It is not only that

we marvel over children like the child Mozart in the past, but in our own day

we have seen a number of these infant prodigies, the limit of whose power was

the smallness of the child hand, and even with that deficient instrument, they

showed

a mastery of the instrument that left behind those who had studied music for

many years. Do we not see in such child genius the mark of past knowledge, of

past power of memory, rather than of learning ?

Or

let us take the Cherniowsky family; three brothers in it have been before the

public

for eleven years, drawing huge audiences by their wonderful music; the

youngest

is now only eighteen, the oldest twenty-two; they have not been taught,

but

have taught themselves, i.e., they have unconsciously remembered. A little

sister

of theirs, now five years old, already plays the violin, and since she

was

a baby the violin has been the one instrument she has loved. Why, if she has

no

memory ?

This

precocious genius, this faculty which accomplishes with ease that which

others

perform with toil and difficulty, is found not only in music. We recall

the

boy Giotto, on the hill-side with his sheep. Nor is it found only in art.

Let

us take that marvelous genius, Dr. Brown, who as a little child, when he was

only

five or six years old, had been able to master dead languages; who, as he

grew

older, picked up science after science, as other children pick up toys with

which

they are amused; who carried an ever-increasing burden of knowledge "

lightly

as a flower" and became one of the most splendid of scientific geniuses,

dealing

with problems that baffled others but that he easily solved, and standing as a

monument of vast constructive scientific power. We find him, according to his

father's account, learning at the age when others are but babies, and using

those extraordinary powers memories of the past persisting into the present.

But

let us take an altogether other class of memory. We meet someone for the

first

time. We feel strongly attracted. There is no outward reason for the

attraction

; we know nothing of his character, of his past; nothing of his

ability,

of his worth; but an overpowering attraction draws us together, and a

life-long,

intimate friendship dates from the first meeting, an instantaneous

attraction,

a recognition of one supremely worthy to be a friend. Many of us

have

had experiences of that kind. Whence come they ? We may have had an equally

strong repulsion, perhaps quite as much outside reason, quite as much apart

from experience.

One

attracts and we love; the other repels and we shrink away. We have no reason

for either love or repulsion. Whence comes it save as a memory

from

the past? A moment's thought shows how such cases are explained from the

standpoint of reincarnation. We have met before, have known each other before.

In the case of a sudden attraction, it is the soul recognising an ancient

friend and comrade across the veil of flesh, the veil of the new body. In the

case of repulsion it is the same soul recognising an ancient enemy, one who

wronged us bitterly, or whom we have wronged; the soul warns us of danger, the

soul warns us of peril, in contact with that ancient foe, and tries to drag

away the unconscious body that does not recognise its enemy, the one whom the

soul knows from past experience to be a peril in the present.

"Instinct" we say; yes, for, as we have seen, instinct is

unconscious, or sub-conscious, memory. A wise man obeys such attractions and

such repulsions; he does not laugh at them as irrational, nor cast them aside

as superstition, as folly; he realises that it is far better for him to keep

out of the way of the man concerning whom the inner warning has arisen, to obey

the repulsion that drives him away from him. For that repulsion indicates the

memory of an ancient wrong, and he is safer out of touch of that man against

whom he feels the repulsion.

Do

we want to eradicate the past wrong, to get rid of the danger? We can do it

better

apart than together. If to that man against whom we feel repulsion we

send

day after day thoughts of pardon and of goodwill; if deliberately,

consciously,

we send messages of love to the ancient enemy, wishing him good,

wishing

him well, in spite of the repulsion that we feel, slowly and gradually

the

pardon and love of the present will erase the memory of the ancient wrong,

and

later we may meet with indifference, or even may become friends, when, by

using

the power of thought, we have wiped out the ancient injury and have made

instead

a bond of brotherhood by thoughts and wishes of good. That is one of the ways

we may utilise the unconscious memories coming to us out of our past.

Again,

sometimes we find in such a first meeting with an ancient friend that we

talk

more intimately to the stranger of an hour ago than we talk to brothers or

sisters

with whom we have been brought up during all our life.

There

must be some explanation of those strange psychological happenings, traces I

put it no more strongly than that worthy of our observation, worthy of our

study; for it is these small things in psychology that point the way to

discoveries of the problems that confront us in that science. Many of us might

add to psychological science by carefully observing, carefully recording,

carefully

working out, all these instinctive impulses, trying to trace out

afterwards

the results in the present and in the future, and thus gather

together

a mass of evidence which may help us to a great extent to understand

ourselves.

What

is the real explanation of the law of memory of events, and this

persistence

in consciousness of attraction or repulsion? The explanation lies in

that

fact of our constitution; the bodies are new, and can only act in

conformity

with past experiences by receiving an impulse from the indwelling

soul

in which the memory of those experiences resides. Just as our children are

born

with a certain developed conscience, which is a moral instinct, just as the

child

of the savage has not the conscience that our children possess previous to

experience

in this life, previous to moral instruction, so is it with these

instincts,

or memories, of the intelligence, which, like the innate moral

instinct

that we call conscience, are based on experience in the past, and hence

are

different in people at different stages of evolution.

A

conscience with a long past behind it is far more evolved, far more ready to

understand

moral differences, than the conscience of a less well evolved

neighbour.

Conscience is not a miraculous implanting; it is the slow growth of

moral

instinct, growing out of experience, built by experience, and becoming

more

and more highly evolved as more and more experience lies behind. And on

this

all true theories of education must be based. We often deal with children

as

though they came into our hands to be moulded at our will. Our lack of

realisation

of the fact that the intelligence of the child, the consciousness of

the

child, is bringing with it the results of past knowledge, both along

intellectual

and moral lines, is a fatal blunder in the education of today. It

is

not a "drawing-out", as the name implies for the name was given by

the

wiser

people of the past.

Education

in these modern days is entirely a pouring in, and therefore it largely fails

in its object. When our teachers realise the fact of reincarnation, when they

see in a child an entity with memories to be aroused and faculties to be drawn

out, then we shall deal with the child as an individual, and not as though

children were turned out by the dozen or the score from some mould into which

they are supposed to have been poured. Then our education will begin to be

individual; we shall study the child before we begin to educate it, instead of

educating it without any study of its faculties.

It

is only by the recognition of its past that we shall realise that we have in

the

child

a soul full of experience, traveling along his own line. Only when we

recognise

that, and instead of the class of thirty or forty, we have the small

class,

where each child is treated individually, only then will education become

a

reality among us, and the men of the future will grow out of the wiser

education

thus given to the children. For the subject is profoundly practical

when

you realise the potencies of daily life. .

Much

light may be thrown on the question of unconscious memories by the study of

memory under trance conditions. All people remember something of their

childhood, but all do not know that in the mesmeric trance a person remembers

much more than he does in the waking consciousness. Memories of events have

sunk below the threshold of the waking consciousness, but they have not been

annihilated, when the consciousness of the external world is stilled, that of

the internal world can assert itself, as low music, drowned in the rattle of

the streets, becomes audible in the stillness of the night. In the depths of

our consciousness, the music of the past is ever playing, and when surface

agitations

are smoothed away, the notes reach our ears. And so in trance we know that

which escapes us when awake. But with regard to childhood there is a thread of

memory sufficient to enable anyone to feel that he, the mature individual, is

identical with the playing and studying child. That thread is lacking where past

lives are concerned, and the feeling of identity, which depends on memory, does

not arise.

Colonel

de Rochas once told me how he had succeeded, with mesmerised patients, in

recovering the memory of babyhood, and gave me a number of instances in which he

had thus pursued memory back into infantile recesses. Nor is the memory only

that of events, for a mesmerised woman, thrown back in memory into childhood

and asked to write, wrote her old childish hand. Interested in this

investigation, I asked Colonel de Rochas to see if he could pass backward

through birth to the previous death, and evoke memory across the gulf which

separates life-period from life-period.

Some

months later he sent me a number of experiments, since published by him, which

had convinced him of the fact of reincarnation. It seems possible that, along

this line, proofs may be gradually accumulated, but much testing and repetition

will be needed, arid a careful shutting out of all external influences.

There

are also cases in which, without the inducing of trance, memories of the

past

survive, and these are found in the cases of children more often than among

grown-up

people. The brain of the child, being more plastic and impressionable,

is

more easily affected by the soul than when it is mature. Let us take a few

cases

of such memories. There was a little lad who showed considerable talent in

drawing and modeling, though otherwise a somewhat dull child. He was taken one

day by his mother to the

his

mother: "O mother, those are the things I used to make". She laughed

at him,

of

course, as foolish people laugh at children, not realising that the unusual

should

be studied and not ridiculed. I do not mean when you were my mother," he

answered. "It was when I had another mother". This was but a sudden

flash of memory, awakened by an outside stimulus; but still it has its value.

We

may take an instance from

frequently

found than in the West, probably because there is not the same

predisposition

to regard them as ridiculous. This, like the preceding, came to

me

from the elder person concerned. He had a little nephew, some five or six

years

of age, and one day, sitting on his uncle's knee, the child began to

prattle

about his mother in the village, and told of a little stream at the end

of

his garden, and how, one day when he had been playing and made himself dirty,

his mother sent him to wash in the stream; he went in too far and woke up

elsewhere. The uncle's curiosity was aroused, and he coaxed details about the

village from the child, and thought he recognised it.

One

day he drove with the child through this village, not telling the child

anything, but the little boy jumped up excitedly and cried out". Oh I this

is my village where I lived, and where I tumbled into the water, and where my

mother lived." He told his uncle where to drive to his cottage, and

running in, cried to a woman therein as his mother. The woman naturally knew

nothing of the child, but asked by the uncle if she had lost a child, she told

him that her little son had been drowned in the stream running by the garden.

There we have a more definite memory, verified by the elder people concerned.

Not

long ago, one of the members of the Theosophical Society, Minister in an

collect

and investigate cases of memory of the past in persons living in his own

neighbourhood.

He found and recorded several cases, investigating each

carefully,

and satisfying himself that the memories were real memories which

could

be tested. One of them I will mention here because it was curious, and

came

into a court of law. It was a case of a man who bad been killed by a

neighbour

who was still living in the village. The accusation of murder was

brought

by the murdered man in his new body! It actually went to trial, and so

the

thing was investigated, and finally the murder was proved to the

satisfaction

of the judge. But judgment was reserved on the ground that the man

could

not bring an action for being murdered, as he was still alive, and the

case

depended upon his testimony alone; so the whole thing fell through.

Memory

of the past can be evolved by gradually sinking down into the depths of

consciousness

by a process deliberately and patiently practised.

Our

mind working in our physical brain is constantly active, and is engaged in

observing the world outside the body. On these observations it reflects and

reasons, and the whole of our normal mental processes have to do with these

daily activities which fill our lives. It is not in this busy region that the

memories of the past can be evoked.

Anyone

who would unveil these must learn so to control his mind as to be able, at

will, to withdraw it from outer objects and from thoughts connected with them,

so as to be able to hold the mind still and empty. It must be wide awake,

alert, and yet utterly quiet and unoccupied. Then, slowly and gradually, within

that mind, emptied of present thought, there arises a fuller, stronger, deeper

consciousness, more vivid, more intensely alive, and this is realised as

oneself; the mind is seen to be only an instrument of this, a tool to be used

at will. When the mind is thus mastered, when it is made subservient to the

higher

consciousness,

then we feel that this new consciousness is the permanent one, in which our

past remains as a memory of events and not only as results in faculty.

We

find that being quiet in the presence of that higher consciousness, asking it

of its past, it will gradually unroll before us the panorama through which it

has itself passed, life after life, and thus enable us to review that past and

to realise it as our own. We find ourselves to be that consciousness; we rise

out of the passing into the permanent, and look back upon our own long past, as

before upon the memory of our childhood. We do not keep its memories always in

mind, but can recover them at will. It is not an ever-present memory, but on

turning our attention to it we can always find it, and we find in that past

others who are the friends of today.

If

we find, as people invariably do find, that the people most closely knit to us

today have been most closely knit to us in the far-off past also, then one

after another we may gather our memories, we may compare them side by side, we

may test them by each other's rememberings, as men of mature age remember their

school-fellows and the incidents of their boyhood and compare those memories

which are common to them both; in that way we gradually learn how we built up

our character, how we have moulded the later lives through which we have

passed. That is within the reach of any one of us who will take the trouble.

I

grant that it takes years, but it can be done. There is, so far as I know, no other

way to the definite recovery of memory. A person may have flashes of memory

from time to time, like the boy with the statues; he may get significant dreams

occasionally, in which some trace of the past may emerge; but to have it under

control, to be able to turn our attention to the past at will and to remember

that needs effort, long, prolonged, patient, persevering; but inasmuch as every

one is a living soul, that memory is within every one, and it is within our

power to awaken it.

No

one need fear that the above practice will weaken the mind, or cause the

student

to become dreamy or less useful in the "practical world". On the

contrary,

such mastery of the mind much strengthens mental grasp and mental

power,

and makes one more effective in the ordinary life of the world. It is not

only

that strength is gained, but the waste of strength is prevented. The mind

does

not "race," as does a machine which continues to go without the

resistance

of

the material on which it should work; for when it has nothing useful to do,

it

stops its activity. Worry is to the mind what racing is to the machine, and

it

wears the mind out where work does not. To control the mind is to have a keen

instrument in good condition, always ready for work. Note how slow many people

are in grasping an idea, how confused, how uncertain. An average man who has

trained his mind to obedience is more effective than a comparatively clever one

who knows naught of such control.

Further,

the conviction, which will gradually arise in the student who studies

these

memories of the past, of the truth of his permanent Self, will

revolutionise

the whole life, both individual and social. If we know ourselves

to

be permanent living beings, we become strong where now we are weak, wise

where

now we are foolish, patient where now we are discontented. Not only does it

make us strong as individuals, but when we come to deal with social problems we

find ourselves able to solve them. We know how to deal with our criminals, who

are only young souls, and instead of degrading them when they come into the

grasp of the law, we treat them as children needing education, needing training

not needing the liberty they do not know how to use, but as children to be

patiently educated helping them to evolve more rapidly because they have come

into our hands.

We

shall treat them with sympathy and not with anger, with gentleness and not with

harshness. I do not mean with a foolish sentimentality which would give them a

liberty they would only abuse to the harming of society ; I mean a steady

discipline which will evolve and strengthen, but has in it nothing brutal,

nothing needlessly painful, an education for the child souls which will help

them to grow.

I

have said how this knowledge would affect the education of children. It would

also change our politics and sociology, by giving us time to build on a

foundation so that the building will be secure.

There

is nothing which so changes our view of life as a knowledge of the past of

which

the present is the outcome, a knowledge how to build so that the building

may

endure in the future. Because things are dark around us and the prospects of

society are gloomy ; because there is war where social prosperity demands

peace, and hatred where mutual assistance ought to be found; because society is

a chaos and not an organism; I find the necessity for pressing this truth of

past lives on the attention of the thoughtful, of those willing to study,

willing to

investigate.

Realising reincarnation as a fact, we can work for brotherhood,

work

for improvement. We realise that every living human being has a right to an

environment

where he can develop his abilities and grow to the utmost of the

faculties

he has brought with him. We understand that society as a whole should

be

as a father and a mother to all those whom it embrace? as its children; that

the

most advanced have duties, have responsibilities, which to a great extent

they

are neglecting today; and that only by understanding, by brotherly love, by

willing

sacrifice, can we emerge from struggle into peace, from poverty into

well-being, from misery and hatred into love and prosperity.

The Theosophical Society,

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky 1831 1891

The Founder of Modern Theosophy

Index of Articles by

By

H P Blavatsky

Is the Desire to Live Selfish?

Ancient Magic in Modern Science

Precepts Compiled by H P Blavatsky

Obras Por H P Blavatsky

En Espanol

Articles about the Life of H P Blavatsky

Nature is infinite in space and

time -- boundless and eternal, unfathomable and ineffable. The all-pervading

essence of infinite nature can be called space, consciousness, life, substance,

force, energy, divinity -- all of which are fundamentally one.

2) The finite and the infinite

Nature is a unity in

diversity, one in essence, manifold in form. The infinite whole is composed of

an infinite number of finite wholes -- the relatively stable and autonomous

things (natural systems or artefacts) that we observe around us. Every natural

system is not only a conscious, living, substantial entity, but is

consciousness-life-substance, of a particular range of density and form.

Infinite nature is an abstraction, not an entity; it therefore does not act or

change and has no attributes. The finite, concrete systems of which it is

composed, on the other hand, move and change, act and interact, and possess

attributes. They are composite, inhomogeneous, and ultimately transient.

3)

Vibration/worlds within worlds

The one essence manifests not

only in infinitely varied forms, and on infinitely varied scales, but also in

infinitely varying degrees of spirituality and substantiality, comprising an

infinite spectrum of vibration or density. There is therefore an endless series

of interpenetrating, interacting worlds within worlds, systems within systems.

The energy-substances of

higher planes or subplanes (a plane being a particular range of vibration) are

relatively more homogeneous and less differentiated than those of lower planes

or subplanes.

Just as boundless space is

comprised of endless finite units of space, so eternal duration is comprised of

endless finite units of time. Space is the infinite totality of worlds within

worlds, but appears predominantly empty because only a tiny fraction of the

energy-substances composing it are perceptible and tangible to an entity at any

particular moment. Time is a concept we use to quantify the rate at which

events occur; it is a function of

change and motion, and

presupposes a succession of cause and effect. Every entity is extended in space

and changes 'in time'.

All change (of position,

substance, or form) is the result of causes; there is no such thing as absolute

chance. Nothing can happen for no reason at all for nothing exists in

isolation; everything is part of an intricate web of causal interconnections and

interactions. The keynote of nature is harmony: every action is automatically

followed by an equal and opposite reaction, which sooner or later rebounds upon

the originator of the initial act. Thus, all our thoughts and deeds will

eventually bring us 'fortune' or 'misfortune' according to the degree to which

they were harmonious or disharmonious. In the long term, perfect justice

prevails in nature.

Because nature is

fundamentally one, and the same basic habits and structural, geometric, and

evolutionary principles apply throughout, there are correspondences between

microcosm and macrocosm. The principle of analogy -- as above, so below -- is a

vital tool in our efforts to understand reality.

All finite systems and their

attributes are relative. For any entity, energy-substances vibrating within the

same range of frequencies as its outer body are 'physical' matter, and finer

grades of substance are what we call energy, force, thought, desire, mind,

spirit, consciousness, but these are just as material to entities on the

corresponding planes as our physical world is to us. Distance and time units

are also relative: an atom is a solar system on its own scale, reembodying perhaps

millions of times in what for us is one second, and our whole galaxy may be a

molecule in some supercosmic entity, for which a million of our years is just a

second. The range of scale is infinite: matter-consciousness is both infinitely

divisible and infinitely aggregative.

All natural systems consist

of smaller systems and form part of larger systems. Hierarchies extend both

'horizontally' (on the same plane) and 'vertically' or inwardly (to higher and

lower planes). On the horizontal level, subatomic particles form atoms, which

combine into molecules, which arrange themselves into cells, which form tissues

and organs, which form part of organisms, which form part of ecosystems, which

form part of planets, solar systems, galaxies, etc. The constitution of worlds

and of the organisms that inhabit them form 'vertical' hierarchies, and can be

divided into several interpenetrating layers or elements, from physical-astral

to psychomental to spiritual-divine, each of which can be further divided.

The human constitution can be

divided up in several different ways: e.g. into a trinity of body, soul, and

spirit; or into 7 'principles' -- a lower quaternary consisting of physical

body, astral model-body, life-energy, and lower thoughts and desires, and an

upper triad consisting of higher mind (reincarnating ego), spiritual intuition,

and inner god. A planet or star can be regarded as a 'chain' of 12 globes, existing

on 7 planes, each globe comprising several subplanes.

The highest part of every

multilevelled organism or hierarchy is its spiritual summit or 'absolute',

meaning a collective entity or 'deity' which is relatively perfected in

relation to the hierarchy in question. But the most 'spiritual' pole of one

hierarchy is the most 'material' pole of the next, superior hierarchy, just as

the lowest pole of one hierarchy is the highest pole of the one below.

Each level of a hierarchical

system exercises a formative and organizing influence on the lower levels

(through the patterns and prototypes stored up from past cycles of activity),

while the lower levels in turn react upon the higher. A system is therefore

formed and organized mainly from within outwards, from the inner levels of its

constitution, which are relatively more enduring and developed than the outer

levels. This inner guidance is sometimes active and selfconscious, as in our

acts of free will (constrained, however, by karmic tendencies from the past),

and sometimes it is automatic and passive, giving rise to our own automatic

bodily functions and habitual and instinctual behavior, and to the orderly,

lawlike operations of nature in general. The 'laws' of nature are therefore the

habits of the various grades of conscious entities that compose reality,

ranging from higher intelligences (collectively

forming the universal mind) to elemental nature-forces.

10) Consciousness and its vehicles

The core of every entity --

whether atom, human, planet, or star -- is a monad, a unit of consciousness-life-substance,

which acts through a series of more material vehicles or bodies. The monad or

self in which the consciousness of a particular organism is focused is animated

by higher monads and expresses itself through a series of lesser monads, each

of which is the nucleus of one of the lower vehicles of the entity in question.

The following monads can be distinguished: the divine or galactic monad, the

spiritual or solar monad, the higher human or planetary-chain monad, the lower

human or globe monad, and the animal, vital-astral, and physical monads. At our

present stage of evolution, we are essentially the lower human monad, and our

task is to raise our consciousness from the animal-human to the spiritual-human

level of it.

Evolution means the

unfolding, the bringing into active manifestation, of latent powers and

faculties 'involved' in a previous cycle of evolution. It is the building of

ever fitter vehicles for the expression of the mental and spiritual powers of

the monad. The more sophisticated the lower vehicles of an entity, the greater

their ability to express the powers locked up in the higher levels of its

constitution. Thus all things are alive and conscious, but the degree of

manifest life and consciousness is extremely varied.

Evolution results from the

interplay of inner impulses and environmental stimuli. Ever building on and

modifying the patterns of the past, nature is infinitely creative.

12) Cyclic evolution/re-embodiment

Cyclic evolution is a

fundamental habit of nature. A period of evolutionary activity is followed by a

period of rest. All natural systems evolve through re-embodiment. Entities are

born from a seed or nucleus remaining from the previous evolutionary cycle of

the monad, develop to maturity, grow old, and pass away, only to re-embody in a

new form after a period of rest. Each new embodiment is the product of past

karma and present choices.

Nothing comes from nothing:

matter and energy can be neither created nor destroyed, but only transformed.

Everything evolves from preexisting material. The growth of the body of an

organism is initiated on inner planes, and involves the transformation of higher

energy-substances into lower, more material ones, together with the attraction

of matter from the environment.

When an organism has

exhausted the store of vital energy with which it is born, the coordinating

force of the indwelling monad is withdrawn, and the organism 'dies', i.e. falls

apart as a unit, and its constituent components go their separate ways. The

lower vehicles decompose on their respective subplanes, while, in the case of

humans, the reincarnating ego enters a dreamlike state of rest and assimilates

the experiences of the previous incarnation. When the time comes for the next

embodiment, the reincarnating ego clothes itself in many of the same atoms of

different grades that it had used previously, bearing the appropriate karmic

impress. The same basic processes of birth, death,

and rebirth apply to all entities, from atoms to humans to stars.

14)

Evolution and involution of worlds

Worlds or spheres, such as

planets and stars, are composed of, and provide the field for the evolution of,

10 kingdoms -- 3 elemental kingdoms, mineral, plant, animal, and human

kingdoms, and 3 spiritual kingdoms. The impulse for a new manifestation of a

world issues from its spiritual summit or hierarch, from which emanate a series

of steadily denser globes or planes; the One expands into the many. During the

first half of the evolutionary cycle (the arc of descent) the energy-substances

of each plane materialize or condense, while during the second half (the arc of

ascent) the trend is towards dematerialization or etherealization, as globes

and entities are reabsorbed into the spiritual hierarch for a period of nirvanic

rest. The descending arc is characterized by the evolution of matter and

involution of spirit, while the ascending arc is characterized by the evolution

of spirit and involution of matter.

In each grand cycle of

evolution, comprising many planetary embodiments, a monad begins as an

unselfconsciousness god-spark, embodies in every kingdom of nature for the

purpose of gaining experience and unfolding its inherent faculties, and ends

the cycle as a self conscious god. Elementals ('baby monads') have no free

choice, but automatically act in harmony with one another and the rest of

nature. In each successive kingdom differentiation and individuality increase,

and reach their peak in the human kingdom with the attainment of

selfconsciousness and a large measure of free will.

In the human kingdom in

particular, self-directed evolution comes into its own. There is no superior

power granting privileges or handing out favours; we evolve according to our

karmic merits and demerits. As we progress through the spiritual kingdoms we

become increasingly at one again with nature, and willingly 'sacrifice' our

circumscribed selfconscious freedoms (especially the freedom to 'do our own

thing') in order to work in peace and harmony with the greater whole of which

we form an integral part. The highest gods of one hierarchy or world-system

begin as elementals in the next. The matter of any plane is composed of

aggregated, crystallized monads in their nirvanic sleep, and the spiritual and

divine entities embodied as planets and stars are the electrons and atomic

nuclei -- the material building blocks -- of worlds on even larger scales.

Evolution is without beginning and without end, an endless adventure through

the fields of infinitude, in which there are always new worlds of experience in

which to become selfconscious masters of life.

There is no absolute

separateness in nature. All things are made of the same essence, have the same

spiritual-divine potential, and are interlinked by magnetic ties of sympathy.

It is impossible to realize our full potential, unless we recognize the

spiritual unity of all living beings and make universal brotherhood the keynote

of our lives.

Hey Look! Theosophy in

Cardiff

Cardiff Theosophical Society

in Wales

Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 1DL

_________________

Wales Picture Gallery

Anglesey Abbey

Bangor

Town Clock

Colwyn

Bay Centre

The

Great Orme

Llandudno

Promenade

Great

Orme Tramway

New

Radnor

Blaenavon

Ironworks

Llandrindod

Wells

Cardiff Theosophical Society

in Wales

Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 1DL

Presteign

Railway

Caerwent Roman Ruins

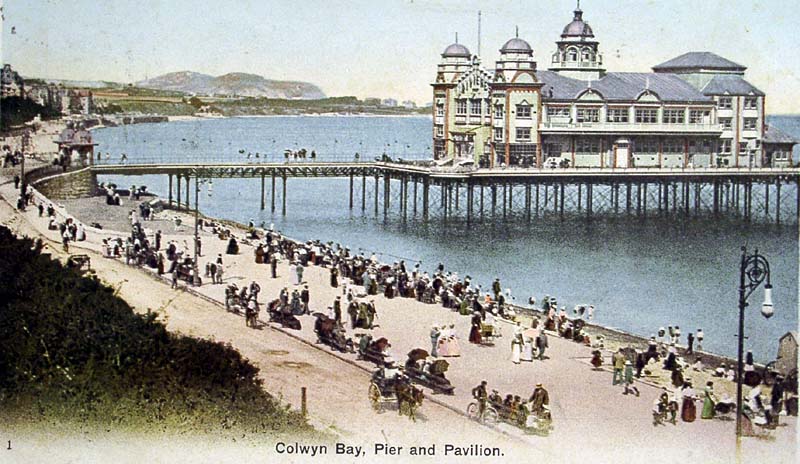

Colwyn

Bay Postcard

Ferndale

in the

Denbigh

National

Museum of

Nefyn

Penisarwaen

Cardiff Theosophical Society

in Wales

Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 1DL