The Writings of Alfred Percy Sinnett

Alfred

Percy Sinnett

1840

-1921

Return to

Esoteric Buddhism Index

Esoteric Buddhism

Chapter 6

Kāma Loca

THE statements already made in reference to the destiny of the

higher human principles at death will pave the way for a comprehension of the

circumstances in which the inferior remnant of these principles finds itself,

after the real Ego has passed either into the Devachanic state, or that

unconscious intervening period of preparation therefore, which corresponds to

physical gestation. The sphere in which such remnants remain for a time is

known to occult science as Kāma loca, the region of desire, not the region in

which desire is developed to any abnormal degree of intensity, as compared with

desire as it attaches to earth life, but the sphere in which that sensation of

desire, which is a part of the earth life, is capable of surviving.

It will be obvious, from what has been said about Devachan, that a

large part of the recollections which accumulate round the human Ego during

life are incompatible in their nature with the pure subjective existence to

which the real, durable, spiritual Ego passes; but they are not necessarily on

that account extinguished or annihilated out of existence. They inhere in

certain molecules of those finer (but not finest) principles, which escape from

the body at death; and just as dissolution separates what is loosely called the

soul from the body, so also it provokes a further separation between the

constituent elements of the soul. So much of the fifth principle, or human

soul, which is in its nature assimilable with, or has gravitated upward

towards, the sixth principle, the spiritual soul, passes with the germ of that

divine soul into the superior region, or state of Devachan, in which it

separates itself almost completely from the attractions of the earth; quite

completely, as far as its own spiritual course is concerned, though it still

has certain affinities with the spiritual aspirations emanating from the earth,

and may sometimes draw these towards itself. But the animal soul, or fourth,

principle (the element of will and desire, as associated with objective

existence), has no upward attraction, and no more passes away from the earth

than the particles of the body consigned to the grave. It is not in the grave,

however, that this fourth principle can be put away. It is not spiritual in its

nature or affinities, but it is not physical in its nature. In its affinities

it is physical, and hence the result. It remains within the actual physical

local attraction of the earth - in the earths atmosphere - or, since it is not

the gases of the atmosphere that are specially to be considered in connection

with the problem in hand, let us say, in Kāma loca.

And with the fourth principle a large part (as regards most of

mankind unfortunately, though a part very variable in its relative magnitude)

inevitably remains. There are plenty of attributes which the ordinary composite

human being exhibits, many ardent feelings, desires, and acts, floods of

recollections, which, even if not concerned with a life as ardent perhaps as

those which have to do with the higher aspirations, are nevertheless

essentially belonging to the physical life, which take time to die. They remain

behind in association with the fourth principle, which is altogether of the

earthly perishable nature, and disperse or fade out, or are absorbed into the

respective universal principles to which they belong just as the body is

absorbed into the earth, in progress of time, and rapidly or slowly, in

proportion to the tenacity of their substance. And where meanwhile is the

consciousness of the individual who has died or dissolved? Assuredly in

Devachan; but a difficulty presents itself to the mind untrained in occult

science, from the fact that a semblance of consciousness inheres in the astral

portion - the fourth principle, with a portion of the fifth - which remains

behind in Kāma loca. The individual consciousness, it is argued, cannot be in

two places at once. But first of all, to a certain extent, it can. As may be

perceived presently, it is a mistake to speak of consciousness, as we

understand the feeling of life, attaching to the astral shell or remnant; but

nevertheless a certain spurious manifestation of consciousness may be

reawakened in the shell, without having any connection with the real

consciousness all the while growing in strength and vitality in the spiritual

sphere. There is no power on the part of the shell of taking in and

assimilating new ideas and initiating courses of action on the basis of those

new ideas. But there is in the shell a survival of volitional impulses imparted

to it during life. The fourth principle is the instrument of volition, though

not volition itself, and impulses imparted to it during life by the higher

principles may run their course and produce results almost indistinguishable for

careless observers from those which would ensue were the four higher principles

really all united, as in life.

The fourth principle, is the vehicle during life of that

essentially mortal consciousness which cannot suit itself to conditions of

permanent existence; but the consciousness even of the lower principles during

life is a very different thing from the vaporous, fleeting and uncertain

consciousness which continues to inhere in them when that which really is

the life, the over-shadowing of them, or their vitalization by the infusion of

the spirit, has ceased, as far as they are concerned. Language cannot render

all the facets of a many-sided idea intelligible at once, any more than a plain

drawing can show all sides of a solid object. And at the first glance different

drawings of the same object from different points of view may seem so unlike as

to be unrecognizable as the same, but none the less, by the time they are put

together in the mind, will their diversities be seen to harmonize. So with these

subtle attributes of the invisible principles of man - no treatise can do more

than discuss their different aspects separately. The various views suggested

must mingle in the readers mind before the complete conception corresponds to

the realities of Nature.

In life the fourth principle is the seat of will and desire, but

it is not will itself. It must be alive, in union with the overshadowing

spirit, or one life, to be thus the agent of that very elevated function of

life - will, in its sublime potency. As already mentioned, the Sanscrit names

of the higher principles connote the idea that they are vehicles of the one

life. Not that the one life is a separable molecular principle itself; it is

the union of all - the influence of the spirit; but in truth the idea is too

subtle for language, perhaps for intellect itself. Its manifestation in the

present case, however, is apparent enough. Whatever the willing fourth

principle may be when alive, it is no longer capable of active will when dead.

But then, under certain abnormal conditions, it may partially recover life for

a time; and this fact it is which explains many, though by no means all, of the

phenomena of spiritualistic mediumship. The elementary, be it remembered - as

the astral shell has generally been called in former occult writings - is

liable to be galvanized for a time in the mediumistic current into a state of

consciousness and life, which may be suggested by the first condition of a

person who, carried into a strange room in a state of insensibility during

illness, wakes up feeble, confused in mind; gazing about with a blank feeling

of bewilderment, taking in impressions, hearing words addressed to him, and

answering vaguely. Such a state of consciousness is unassociated with the notions

of past or future. It is an automatic consciousness, derived from the medium. A

medium, be it remembered, is a person whose principles are loosely united and

susceptible of being borrowed by other beings, or by floating principles,

having an attraction for some of them or some part of them. Now what happens in

the case of a shell drawn into the neighbourhood of a person so constituted?

Suppose the person from whom the shell has been cast, died with some strong

unsatisfied desire, not necessarily of an unholy sort, but connected entirely

with the earth life, a desire, for example, to communicate some fact to a still

living person. Certainly the shell does not go about in Kāma loca with a

persistent intelligent conscious purpose of communicating that fact; but,

amongst others, the volitional impulse to do this has been infused into the

fourth principle, and while the molecules of that principle remain in

association, (and that may be for many years,) they only need a partial

galvanization into life again, to become operative in the direction of the

original impulse. Such a shell comes into contact with a medium (not so

dissimilar in nature from the person who had died as to render a rapport

impossible), and something from the fifth principle of the medium associates

itself with the wandering fourth principle, and sets the original impulse to

work. So much consciousness and so much intelligence as may be required to

guide the fourth principle in the use of the immediate means of communication

at hand - a slate and pencil, or a table to rap upon - is borrowed from the

medium, and then the message given may be the message which the dead person

originally ordered his fourth principle to give, so to speak, but which the

shell has never till then had an opportunity of giving. It may be argued that

the production of writing on a closed slate, or of raps on a table without the

use of a knuckle or a stick, is itself a feat of a marvellous nature,

bespeaking a knowledge on the part of the communicating intelligence of powers

in Nature we in physical life know nothing about. But the shell is itself in

the astral world; in the realm of such powers. A phenomenal manifestation is

its natural mode of dealing. It is no more conscious of producing a wonderful

result by the use of new powers acquired in a higher sphere of existence, than

we are conscious of the forces by which in life the volitional impulse is

communicable to nerves and muscles.

But, it may be objected, the communicating intelligence at a

spiritual séance will constantly perform remarkable feats for no other

than their own sake, to exhibit the power over natural forces which it

possesses. The reader will please remember, however, that occult science is

very far from saying that all the phenomena of spiritualism are traceable to

one class of agents. Hitherto in this treatise little has been said of the

elementals, those semi-intelligent creatures of the astral light, who belong

to a wholly different

Returning to a consideration of the ex-human shells in Kāma loca,

it may be argued that their behaviour in spiritual séances is not

covered by the theory that they have had some message to deliver from their

late master, and have availed themselves of the mediumship present, to deliver

it. Apart altogether from phenomena that may be put aside as elemental pranks,

we sometimes encounter a continuity of intelligence on the part of the

elementary or shell that bespeaks much more than the survival of impulses from

the former life. Quite so; but with portions of the mediums fifth principle

conveyed into it, the fourth principle is once more an instrument in the hands

of a master. With a medium entranced so that the energies of the fifth

principle are conveyed into the wandering shell to a very large extent, the

result is that there is a very tolerable revival of consciousness in the shell

for the time being, as regards the given moment. But what is the nature of such

consciousness, after all? Nothing more, really, than a reflected light. Memory

is one thing, and perceptive faculties quite another. A madman may remember very

clearly some portions of his past life; yet he is unable to perceive anything

in its true light, for the higher portion of his Manas, fifth, and Buddhi,

sixth, principles, are paralysed in him and have left him. Could an animal - a

dog, for instance - explain himself, he could prove that his memory, in direct

relation to his canine personality, is as fresh as his masters; nevertheless,

his memory and instinct cannot be called perceptive faculties.

Once that a shell is in the aura of a medium, he will perceive,

clearly enough, whatever he can perceive through the borrowed principles of the

medium, and through organs in magnetic sympathy therewith; but this will not

carry him beyond the range of the perceptive faculties of the medium, or of

some one else present in the circle. Hence the often rational and sometimes

highly intelligent answers he may give, and hence, also, his invariably

complete oblivion of all things unknown to that medium or circle, or not found

in the lower recollections of his late personality, galvanized afresh by the

influences under which he is placed. The shell of a highly intelligent,

learned, but utterly unspiritual man, who died a natural death, will last

longer than those of weaker temperament, and (the shadow of his own memory

helping) he may deliver, through trance-speakers, orations of no contemptible

kind. But these will never be found to relate to anything beyond the subjects

he thought much and earnestly of during life, nor will any word ever fall from

him indicating a real advance of knowledge.

It will easily be seen that a shell, drawn into the mediumistic

current, and getting into rapport with the mediums fifth principle, is

not by any means sure to be animated with a consciousness (even for what such

consciousness are worth) identical with the personality of the dead person from

whose higher principles it was shed. It is just as likely to reflect some quite

different personality, caught from the suggestions of the mediums mind. In

this personality it will perhaps remain and answer for a time; then some new

current of thought thrown into the minds of the people present, will find its

echo in the fleeting impressions of the elementary, and his sense of identity

will begin to waver; for a little while it flickers over two or three

conjectures, and ends by going out altogether for a time. The shell is once

more sleeping in the astral light, and may be unconsciously wafted in a few

moments to the other ends of the earth.

Besides the ordinary elementary or shell of the kind just

described, Kāma loca is the abode of another class of astral entities, which

must be taken into account if we desire to comprehend the various conditions

under which human creatures may pass from this life to others. So far we have

been examining the normal course of events, when people die in a natural

manner. But an abnormal death will lead to abnormal consequences. Thus, in the

case of persons committing suicide, and in that of persons killed by sudden

accident, results ensue which differ widely from those following natural

deaths. A thoughtful consideration of such cases must show, indeed, that in a

world governed by rule and law, by affinities working out their regular effects

in that deliberate way which Nature favours, the case of a person dying a

sudden death at a time when all his principles are firmly united, and ready to

hold together for twenty, forty, or sixty years, whatever the natural remainder

of his life would be, must surely be something different from that of a person

who, by natural processes of decay, finds himself, when the vital machine

stops, readily separable into his various principles, each prepared to travel

their separate ways. Nature, always fertile in analogies, at once illustrates

the idea by showing us a ripe and an unripe fruit. From out of the first the

inner stone will come away as cleanly and easily as a hand from a glove, while

from the unripe fruit the stone can only be torn with difficulty, half the pulp

clinging to its surface. Now, in the case of the sudden accidental death or of

the suicide, the stone has to be torn from the unripe fruit. There is no

question here about the moral blame which may attach to the act of suicide.

Probably, in the majority of cases, such moral blame does attach to it, but

that is a question of Karma which will follow the person concerned into the

next re-birth, like any other Karma, and has nothing to do with the immediate

difficulty such person may find in getting himself thoroughly and wholesomely

dead. This difficulty is manifestly just the same, whether a person kills

himself, or is killed in the heroic discharge of duty, or dies the victim of an

accident over which he has no control whatsoever.

As an ordinary rule, when a person dies, the long account of Karma

naturally closes itself - that is to say, the complicated set of affinities

which have been set up during life in the first durable principle, the fifth,

is no longer susceptible of extension. The balance-sheet, so to speak, is made

out afterwards, when the time comes for the next objective birth; or, in other

words, the affinities long dormant in Devachan, by reason of the absence there

of any scope for their action, assert themselves as soon as they come in

contact once more with physical existence. But the fifth principle, in which

these affinities are grown, cannot be separated, in the case of the person

dying prematurely, from the earthly principle - the fourth. The elementary,

therefore, which finds itself in Kāma loca, on its violent expulsion from the

body is not a mere shell - it is the person himself, who was lately alive, minus

nothing but the body. In the true sense of the word, he is not dead at all.

Certainly elementaries of this kind may communicate very effectually

at spiritual séances at their own heavy cost; for they are unfortunately

able, by reason of the completeness of their astral constitution, to go on

generating Karma, to assuage their thirst for life at the unwholesome spring of

mediumship. If they were of a very material sensual type in life, the

enjoyments they will seek will be of a kind the indulgence of which in their

disembodied state may readily be conceived even more prejudicial to their Karma

than similar indulgences would have been in life. In such cases facilis est

descensus. Cut off in the full flush of earthly passions which bind them to

familiar scenes, they are enticed by the opportunity which mediums afford for

the gratification of these vicariously. They become the incubi and succubi of mediaeval

writing, demons of thirst and gluttony, provoking their victims to crime. A

brief essay on this subject, which I wrote last year, and from which I have

reproduced some of the sentences just given, appeared in the Theosophist,

with a note, the authenticity of which I have reason to trust, and the tenor of

which was as follows: -

The variety of states after death is greater if possible than the

variety of human lives upon this earth. The victims of accident do not

generally become earth walkers, only those falling into the current of

attraction who die full of some engrossing earthly passion, the selfish,

who have never given a thought to the welfare of others. Overtaken by death in

the consummation, whether real or imaginary, of some master passion of their

lives, the desire remaining unsatisfied, even after a full realization, and

they still craving for more, such personalities can never pass beyond the earth

attraction to wait for the hour of deliverance in happy ignorance and full

oblivion. Among the suicides, those to whom the above statement about provoking

their victims to crime, &c., applies, are that class who commit the act, in

consequence of a crime, to escape the penalty of human law or their own

remorse. Natural law cannot be broken with impunity; the inexorable causal

relation between action and result has its full sway only in the world of

effects, the Kāma loca, and every case is met there by an adequate punishment,

and in a thousand ways, that would require volumes even to describe them

superficially.

Those who wait for the hour of deliverance in happy ignorance and

full oblivion are of course such victims of accident as have already on earth

engendered pure and elevated affinities, and after death are as much beyond the

reach of temptation in the shape of mediumistic currents as they would have

been inaccessible in life to common incitements to crime.

Entities of another kind occasionally to be found in Kāma loca

have yet to be considered. We have followed the higher principles of persons

recently dead, observing the separation of the astral dross from the

spirituality durable portion; that spirituality durable portion being either

holy or Satanic in its nature, and provided for in Devachan or Avitchi

accordingly. We have examined the nature of the elementary shell cast off and

preserving for a time a deceptive resemblance to a true entity; we have paid

attention also to the exceptional cases of real four-principled beings in Kāma

loca who are the victims of accident or suicide. But what happens to a

personality which has absolutely no atom of spirituality, no trace of spiritual

affinity in its fifth principle, either of the good or bad sort? Clearly in

such a case there is nothing for the sixth principle to attract to itself. Or,

in other words, such a personality has already lost its sixth principle by the

time death comes. But Kāma loca is no more a sphere of existence for such a

personality than the subjective world; Kāma loca may be permanently inhabited

by astral beings, by elementals, but can only be an antechamber to some other

state for human beings. In the case imagined, the surviving personality is

promptly drawn into the current of its future destinies, and these have nothing

to do with this earths atmosphere or with Devachan, but with that eighth

sphere of which occasional mention will be found in older occult writings. It

will have been unintelligible to ordinary readers hitherto why it was called

the eighth sphere, but since the explanation, now given out for the first

time, of the sevenfold constitution of our planetary system, the meaning will

be clear enough. The spheres of the cyclic process of evolution are seven in

number, but there is an eighth in connection with our earth, our earth being,

it will be remembered, the turning-point in the cyclic chain, and this eighth

sphere is out of circuit, a cul de sac, and the bourne from which it may

be truly said no traveller returns.

It will readily be guessed that the only sphere connected with our

planetary chain, which is lower than our own in the scale, having spirit at the

top and matter at the bottom, must itself be no less visible to the eye and to

optical instruments than the earth itself, and as the duties which this sphere

has to perform in our planetary system are immediately associated with this

earth, there is not much mystery left now in the riddle of the eighth sphere,

nor as to the place in the sky where it may be sought. The conditions of

existence there, however, are topics on which the adepts are very reserved in

their communications to uninitiated pupils, and concerning these I have for the

present no further information to give.

One statement though is definitely made-viz., that such a total

degradation of a personality as may suffice to draw it, after death, into the

attraction of the eighth sphere, is of very rare occurrence. From the vast

majority of lives there is something which the higher principles may draw to

themselves, something to redeem the page of existence just passed from total

destruction, and here it must be remembered that the recollections of life in

Devachan, very vivid as they are, as far as they go, touch only those episodes

in life that are productive of the elevated sort of happiness of which alone

Devachan is qualified to take cognizance, whereas the life from which, for the

time being, the cream is thus skimmed, may come to be remembered eventually in

all its details quite fully. That complete remembrance is only achieved by the

individual at the threshold of a far more exalted spiritual state than that

which we are now concerned with; one which is attained far later on in the

progress of vast cycles of evolution. Each one of the long series of lives that

will have been passed through will then be, as it were, a page in a book to

which the possessor can turn back at pleasure, even though many such pages will

then seem to him most likely, very dull reading, and will not be frequently

referred to. It is this revival eventually of recollection concerning all the

long-forgotten personalities that is really meant by the doctrine of the

Resurrection. But we have no time at present to stop and unravel the enigmas of

symbolism as bearing upon the teachings at present under conveyance to the

reader. It may be worth while to do this as a separate undertaking at a later

period; but meanwhile, to revert to the narrative of how the facts stand, it

may be explained that in the whole book of pages, when at last the

resurrection has been accomplished, there will be no entirely infamous pages;

for even if any given spiritual individuality has occasionally, during its

passage through this world, been linked with personalities so deplorably and

desperately degraded that they have passed completely into the attraction of

the lower vortex, that spiritual individuality in such cases will have

retained, in its own affinities, no trace or taint of them. Those pages will,

as it were, have been cleanly torn out from the book. And, as at the end of the

struggle, after crossing Kāma loca, the spiritual individuality will have

passed into the unconscious gestation state from which, skipping the Devachan

state, it will be directly (though not immediately in time) reborn into its

next life of objective activity, all the self-consciousness connected with that

existence will have passed into the lower world, there eventually to perish

everlastingly; an expression of which, as of so many more, modern theology has

proved a faithless custodian, making pure nonsense out of psycho-scientific

facts.

ANNOTATIONS

There is no part of the present volume which I now regard as in so

much urgent need of amplification as the two chapters which have just been

passed. The Kāma loca stage of existence, and that higher region or state of

Devachan, to which it is but the antechamber, were, designedly I take it, left

by our teachers in the first instance in partial obscurity, in order that the

whole scheme of evolution might be the better understood. The spiritual state

which immediately follows our present physical life, is a department of Nature,

the study of which is almost unhealthily attractive for every one who once

realizes that some contact with it - some processes of experiment with its

conditions - are possible even during this life. Already we can to a certain

extent discern the phenomena of that state of existence into which a human

creature passes at the death of the body. The experience of spiritualism has

supplied us with facts concerning it in very great abundance. These facts are

but too highly suggestive of theories and inferences which seem to reach the

ultimate limits of speculation, and nothing but the bracing mental discipline

of esoteric study in its broadest aspect will protect any mind addressed to the

consideration of these facts from conclusions which that study shows to be

necessarily erroneous. For this reason, theosophical inquirers have nothing to

regret as far as their own progress in spiritual science is at stake, in the

circumstances which have hitherto induced them to be rather neglectful of the

problems that have to do with the state of existence next following our own. It

is impossible to exaggerate the intellectual advantages to be derived from

studying the broad design of Nature throughout those vast realms of the future

which only the perfect clairvoyance of the adepts can penetrate, before going

into details regarding that spiritual foreground, which is partially accessible

to less powerful vision, but liable, on a first acquaintance, to be mistaken

for the whole expanse of the future.

The earlier processes, however, through which the soul passes at

death, may be described at this date somewhat more fully than they are defined

in the foregoing chapter. The nature of the struggle that takes place in Kāma

loca between the upper and lower duads may now, I believe, be apprehended more

clearly than at first. That struggle appears to be a very protracted and

variegated process, and to constitute,- not as some of us may have conjectured

at first, an automatic or unconscious assertion of affinities or forces quite

ready to determine the future of the spiritual monad at the period of death, -

but a phase of existence which may be, and in the vast majority of cases is

more than likely to be, continued over a considerable series of years. And

during this phase of existence it is quite possible for departed human entities

to manifest themselves to still living persons through the agency of spiritual

mediumship, in a way which may go far towards accounting for, if it does not

altogether vindicate, the impressions that spiritualists derive from such

communications.

But we must not conclude too hastily that the human soul going

through the struggle or evolution of Kāma loca is in all respects what the

first glance at the position, as thus defined, may seem to suggest. First of

all, we must beware of too grossly materializing our conception of the

struggle, by thinking of it as a mechanical separation of principles. There is

a mechanical separation involved in the discard of lower principles when the

consciousness of the Ego is firmly seated in the higher. Thus at death the body

is mechanically discarded by the soul, which (in union, perhaps, with

intermediate principles), may actually be seen by some clairvoyants of a high

order to quit the tenement it needs no longer. And a very similar process may

ultimately take place in Kāma loca itself, in regard to the matter of the

astral principles. But postponing this consideration for a few moments, it is

important to avoid supposing that the struggle of Kāma loca does itself constitute

this ultimate division of principles, or second death upon the astral plane.

The struggle of Kāma loca is in fact the life of the entity in

that phase of existence. As quite correctly stated in the text of the foregoing

chapter, the evolution taking place during that phase of existence is not

concerned with the responsible choice between good and evil which goes on

during physical life. Kāma loca is a portion of the great world of effects, -

not a sphere in which causes are generated (except under peculiar

circumstances). The Kāma loca entity, therefore, is not truly master of his own

acts; he is rather the sport of his own already established affinities. But

these are all the while asserting themselves, or exhausting themselves, by

degrees, and the Kāma loca entity has an existence of vivid consciousness

of one sort or another the whole time. Now a moments reflection will show that

those affinities, which are gathering strength and asserting themselves, have

to do with the spiritual aspirations of the life last experienced, while

those which are exhausting themselves have to do with its material

tastes, emotions, and proclivities. The Kāma loca entity, be it remembered, is

on his way to Devachan, or, in other words, is growing into that state which is

the Devachanic state, and the process of growth is accomplished by action and

reaction, by ebb and flow, like almost every other in Nature, - by a species of

oscillation between the conflicting attractions of matter and spirit. Thus the

Ego advances towards Heaven, so to speak, or recedes towards earth, during his

Kāma loca existence, and it is just this tendency to oscillate between the two

poles of thought or condition, that brings him back occasionally within the

sphere of the life he has just quitted.

It is not by any means at once that his ardent sympathies with

that life are dissipated. His sympathies with the higher aspects of that life,

be it remembered, are not even on their way to dissipation. For instance, in what

is here referred to as earthly affinity, we need not include the exercise of

affection, which is a function of Devachanic existence in a pre-eminent degree.

But perhaps even in regard to his affections there may be earthly and spiritual

aspects of these, and the contemplation of them, with the circumstances and

surroundings of the earth-life, may often have to do with the recession towards

earth-life of the Kāma loca entity referred to above.

Of course it will be apparent at once that the intercourse which

the practice of spiritualism sets up between the Kāma loca entities as here in

view, and the friends they have left on earth, must go on during those periods

of the souls existence in which earth memories engage its attention; and there

are two considerations of a very important nature which arise out of this

reflection.

1st. While its attention is thus directed, it is turned

away from the spiritual progress on which it is engaged during its oscillations

in the other direction. It may fairly well remember, and in conversation refer

to, the spiritual aspirations of the life on earth, but its new spiritual

experiences appear to be of an order that cannot be translated back into terms

of the ordinary physical intellect, and, besides that, to be not within the

command of the faculties which are in operation in the soul during its

occupation with old-earth memories. The position might be roughly symbolized,

but only to a very imperfect extent, by the case of a poor emigrant, whom we

may imagine prospering in his new country, getting educated there, concerning

himself with its public affairs and discoveries, philanthropy, and so on. He

may keep up an interchange of letters with his relations at home, but he will

find it difficult to keep them au courant with all that has come to be

occupying his thoughts. The illustration will only fully apply to our present

purpose, however, if we think of the emigrant as subject to a psychological law

which draws a veil over his understanding when he sits down to write to his

former friends, and restores him during that time to his former mental

condition. He would then be less and less able to write about the old topics as

time went on, for they would not only be below the level of those to the

consideration of which his real mental activities had risen, but would to a

great extent have faded from his memory. His letters would be a source of

surprise to their recipients, who would say to themselves that it was certainly

so-and-so who was writing, but that he had grown very dull and stupid compared

to what he used to be before he went abroad.

2ndly. It must be borne in mind that a very well-known law of

physiology, according to which faculties are invigorated by use and atrophied

by neglect, applies on the astral as well as on the physical plane. The soul in

Kāma loca, which acquires the habit of fixing its attention on the memories of

the life it has quitted, will strengthen and harden those tendencies which are

at war with its higher impulses. The more frequently it is appealed to by the

affection of friends still in the body to avail itself of the opportunities

furnished by mediumship for manifesting its existence on the physical plane,

the more vehement will be the impulses which draw it back to physical life, and

the more serious the retardation of its spiritual progress. This consideration

appears to involve the most influential motive which leads the representatives

of Theosophical teaching to discountenance and disapprove of all attempts to

hold communication with departed souls by means of the spiritual séance. The

more such communications are genuine the more detrimental they are to the

inhabitants of Kāma loca concerned with them. In the present state of our

knowledge it is difficult to determine with confidence the extent to which the

Kāma loca entities are thus injured. And we may be tempted to believe that in

some cases the great satisfaction derived by the living persons who

communicate, may outweigh the injury so inflicted on the departed soul. This

satisfaction, however, will only be keen in proportion to the failure of the

still living friend to realize the circumstances under which the communication

takes place. At first, it is true, very shortly after death, the still vivid

and complete memories of earth-life may enable the Kāma loca entity to manifest

himself as a personage very fairly like his deceased self, but from the moment

of death the change in the direction of his evolution sets in. He will, as

manifesting on the physical plane, betray no fresh fermentation of thought in

his mind. He will never, in that manifestation, be any wiser, or higher in the

scale of Nature, than he was when he died; on the contrary, he must become less

and less intelligent, and apparently less instructed than formerly, as time goes

on. He will never do himself justice in communication with the friends left

behind, and his failure in this respect will grow more and more painful by

degrees.

Yet another consideration operates to throw a very doubtful light

on the wisdom or propriety of gratifying a desire for intercourse with deceased

friends. We may say, never mind the gradually fading interest of the friend who

has gone before, in the earth left behind; while there is anything of his or

her old self left to manifest itself to us, it will be a delight to communicate

even with that. And we may argue that if the beloved person is delayed a little

on his way to Heaven by talking with us, he or she would be willing to make

that sacrifice for our sake. The point overlooked here is, that on the astral,

just as on the physical plane, it is a very easy thing to set up a bad habit.

The soul in Kāma loca once slaking a thirst for earthly intercourse at the

wells of mediumship will have a strong impulse to fall back again and again on

that indulgence. We may be doing a great deal more than diverting the souls

attention from its own proper business by holding spiritualistic relations with

it. We may be doing it serious and almost permanent injury. I am not

affirming that this would invariably or generally be the case, but a severe

view of the ethics of the subject must recognize the dangerous possibilities

involved in the course of action under review. On the other hand, however, it

is plain that cases may arise in which the desire for communication chiefly

asserts itself from the other side: that is to say, in which the departed soul

is laden with some unsatisfied desire - pointing possibly towards the

fulfilment of some neglected duty on earth - the attention to which on the part

of still-living friends may have an effect quite the reverse of that attending

the mere encouragement of the Kāma loca entity in the resumption of its old

earthly interests. In such cases the living friends may, by falling in with its

desire to communicate, be the means, indirectly, of smoothing the path of its

spiritual progress. Here again, however, we must be on our guard against the

delusive aspect of appearances. A wish manifested by an inhabitant of Kāma loca

may not always be the expression of an idea then operative in his mind. It may

be the echo of an old, perhaps of a very old, desire, then for the first time

finding a channel for its outward expression. In this way, although it would be

reasonable to treat as important an intelligible wish conveyed to us from Kāma

loca by a person only lately deceased, it would be prudent to regard with great

suspicion such a wish emanating from the shade of a person who had been dead a

long time, and whose general demeanour as a shade did not seem to convey the

notion that he retained any vivid consciousness of his old personality.

The recognition of all these facts and possibilities of Kāma loca

will, I think, afford theosophists a satisfactory explanation of a good many

experiences connected with spiritualism which the first exposition of the

esoteric doctrine, as bearing on this matter, left in much obscurity.

It will be readily perceived that as the soul slowly clears itself

in Kāma loca of the affinities which retard its Devachanic development, the

aspect it turns towards the earth is more and more enfeebled, and it is

inevitable that there must always be in Kāma loca an enormous number of

entities nearly ripe for a complete mergence in Devachan, who on that very

account appear to an earthly observer in a state of advanced decrepitude. These

will have sunk, as regards the activity of their lower astral principles, into

the condition of the altogether vague and unintelligible entities, which,

following the example of older occult writers, I have referred to as shells

in the text of this chapter. The designation, however, is not altogether a

happy one. It might have been better to have followed another precedent, and to

have called them shades, but either way their condition would be the same.

All the vivid consciousness inhering, as they left the earth, in the principles

appropriately related to the activities of physical life, has been transferred

to the higher principles which do not manifest at séances. Their memory of

earth-life has almost become extinct. Their lower principles are in such cases

only reawakened by the influences of the mediumistic current into which they

may be drawn, and they become then little more than astral looking-glasses, in

which the thoughts of the medium or sitters at the séance are reflected. If we

can imagine the colours on a painted canvas sinking by degrees into the

substance of the material, and at last re-emerging in their pristine brilliancy

on the other side, we shall be conceiving a process which might not have

destroyed the picture, but which would leave a gallery in which it took place,

a dreary scene of brown and meaningless backs, and that is very much what the

Kāma loca entities become before they ultimately shed the very material on

which their first astral consciousness operated, and pass into the wholly

purified Devachanic condition.

But this is not the whole of the story which teaches us to regard

manifestations coming from Kāma loca with distrust. Our present comprehension

of the subject enables us to realize that when the time arrives for that second

death on the astral plane, which releases the purified Ego from Kāma loca

altogether and sends it onward to the Devachanic state - something is left

behind in Kāma loca which corresponds to the dead body bequeathed to the earth

when the soul takes its first flight from physical existence. A dead astral

body is in fact left behind in Kāma loca, and there is certainly no impropriety

in applying the epithet shell to that residuum. The true shell in that

state disintegrates in Kāma loca before very long, just as the true body left

to the legitimate processes of Nature on earth would soon decay and blend its

elements with the general reservoirs of matter of the order to which they

belong. But until that disintegration is accomplished, the shell which the real

Ego has altogether abandoned, may even in that state be mistaken

sometimes at spiritual séances for a living entity. It remains for a time an

astral looking-glass, in which mediums may see their own thoughts reflected,

and take these back, fully believing them to come from an external source.

These phenomena in the truest sense of the term are galvanized

astral corpses; none the less so, because until they are actually disintegrated

a certain subtle connection will subsist between them and the true Devachanic

spirit; just as such a subtle communication subsists in the first instance

between the Kāma loca entity, and the dead body left on earth. That

last-mentioned communication is kept up by the finely-diffused material of the

original third principle, or linga sharira, and a study of this branch

of the subject will, I believe, lead us up to a better comprehension than we

possess at present of the circumstances under which materializations are

sometimes accomplished at spiritual séances. But without going into that

digression now, it is enough to recognize that the analogy may help to show

how, between the Devachanic entity and the discarded shell in Kāma loca a

similar connection may continue for awhile, acting, while it lasts, as a drag

on the higher spirit, but perhaps as an after-glow of sunset on the shell. It

would surely be distressing, however, in the highest degree, to any living

friend of the person concerned, to get, through clairvoyance, or in any other

way, sight or cognition of such a shell, and to be led into mistaking it for

the true entity.

The comparatively clear view of Kāma loca which we are now enabled

to take, may help us to employ terms relating to its phenomena with more

precision than we have hitherto been able to attain. I think if we adopt one

new expression, astral soul, as applying to the entities in Kāma loca who

have recently quitted earth-life, or who for other reasons still retain, in the

aspect they turn back towards earth, a large share of the intellectual

attributes that distinguished them on earth, we shall then find the other terms

in use already, adequate to meet our remaining emergencies. Indeed, we may then

get rid entirely of the inconvenient term elementary, liable to be confused

with elemental, and singularly inappropriate to the beings it describes. I

would suggest that the astral soul as it sinks (regarded from our point of

view) into intellectual decrepitude, should be spoken of in its faded condition

as a shade, and that the term shell should be reserved for the true shells or

astral dead bodies which the Devachanic spirit has finally quitted.

We are naturally led in studying the law of spiritual growth in

Kāma loca to inquire how long a time may probably elapse before the transfer of

consciousness from the lower to the higher principles of the astral soul may be

regarded as complete; and as usual, when we come to figures relating to the

higher processes of Nature, the answer is very elastic. But I believe the

esoteric teachers of the East declare that as regards the average run of

humanity - for what may be called, in a spiritual sense, the great middle

classes of humanity - it is unusual that a Kāma loca entity will be in a

position to manifest as such for more than twenty-five to thirty years. But on

each side of this average the figures may run up very considerably. That is to

say, a very ignoble and besotted human creature may hang about in Kāma loca for

a much longer time for want of any higher principles sufficiently developed to

take up his consciousness at all, and at the other end of the scale the very

intellectual and mentally-active soul may remain for very long periods in Kāma

loca (in the absence of spiritual affinities in corresponding force), by reason

of the great persistence of forces and causes generated on the higher plane of

effects, though mental activity could hardly be divorced in this way from

spirituality except in cases where it was exclusively associated with worldly

ambition. Again, while Kāma loca periods may thus be prolonged beyond the

average from various causes, they may sink to almost infinitesimal brevity when

the spirituality of a person dying at a ripe old age, and at the close of a

life which has legitimately fulfilled its purpose, is already far advanced.

There is one other important possibility connected with

manifestations reaching us by the usual channels of communication with Kāma

loca, which it is desirable to notice here, although from its nature the

realization of such a possibility cannot be frequent. No recent students of

theosophy can expect to know as yet very much about the conditions of existence

which await adepts who relinquish the use of physical bodies on earth. The

higher possibilities open to them appear to me quite beyond the reach of intellectual

appreciation. No man is clever enough, by virtue of the mere cleverness seated

in a living brain, to understand Nirvana; but it would appear that adepts in

some cases elect to pursue a course lying midway between re-incarnation and the

passage into Nirvana, and in the higher regions of Devachan; that is to say, in

the arupa state of Devachan may await the slow advance of human

evolution towards the exalted condition they have thus attained. Now an adept

who has thus become a Devachanic spirit of the most elevated type would not be

cut off by the conditions of his Devachanic state - as would be the case with a

natural Devachanic spirit passing through that state on his way to

reincarnation - from manifesting his influence on earth. His would certainly not

be an influence which would make itself felt by the instrumentality of any

physical signs to mixed audiences, but it is not impossible that a medium of

the highest type - who would more properly be called a seer - might be thus influenced.

By such an Adept spirit, some great men in the worlds history may from time to

time have been overshadowed and inspired, consciously or unconsciously as the

case may have been.

The disintegration of shells in Kāma-loca will inevitably suggest

to any one who endeavours to comprehend the process at all, that there must be

in Nature some general reservoirs of the matter appropriate to that sphere of

existence, corresponding to the physical earth and its surrounding elements

into which our own bodies are resigned at death. The grand mysteries on which

this consideration impinges will claim a far more exhaustive investigation than

we have yet been enabled to undertake; but one broad idea connected with them

may usefully be put forward without further delay. The state of Kāma-loca is

one which has its corresponding orders of matter in manifestation round it. I

will not here attempt to go into the metaphysics of the problem, which might

even lead us to discard the notion that astral matter need be any less real and

tangible than that which appeals to our physical senses. It is enough for the

present to explain that the propinquity of Kāma loca to the earth which is so

readily made apparent by spiritualistic experience, is explained by Oriental

teaching to arise from this fact, - that Kāma-loca is just as much in and of

the earth as, during our lives, our astral soul is in and of the living man.

The stage of Kāma-loca, in fact, the great realm of matter in the appropriate

state which constitutes Kāma-loca and is perceptible to the senses of astral

entities, as also to those of many clairvoyants, is the fourth principle of

man. For the earth has its seven principles like the human creatures who

inhabit it. Thus, the Devachanic state corresponds to the fifth principle of

the earth, and Nirvana to the sixth principle.

Return to

Esoteric Buddhism Index

The Theosophical Society,

For more info on Theosophy

Try these

Daves Streetwise Theosophy

Boards

Cardiff

Lodges Instant Guide to Theosophy

One

Liners & Quick Explanations

The

Most Basic Theosophy Website in the Universe

If you run a Theosophy Group

you can use

this as an introductory

handout

Try these if you are

looking for a local group

UK Listing of

Theosophical Groups

Worldwide

Directory of Theosophical Links

Cardiff Theosophical Society

in Wales

Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 1DL

_________________

Wales Picture Gallery

The

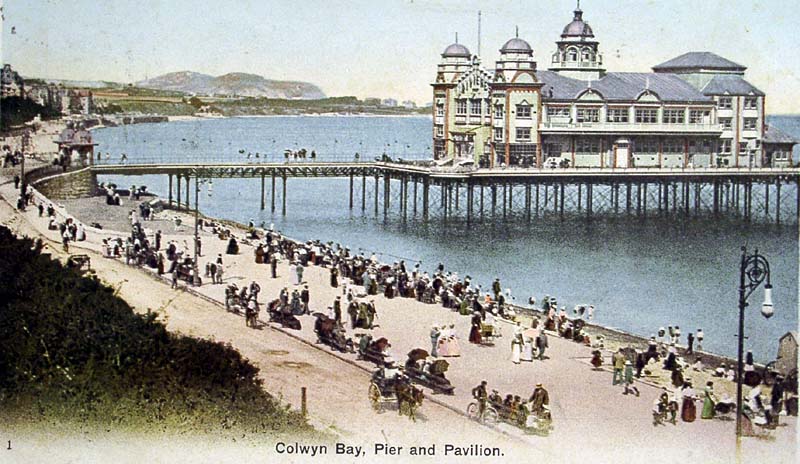

Great Orme

Llandudno

Promenade

Great

Orme Tramway

New

Radnor

Blaenavon

Ironworks

Llandrindod

Wells

Cardiff Theosophical Society

in Wales

Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 1DL

Presteign

Railway

Caerwent Roman Ruins

Cardiff, Wales, UK, CF24

1DL

Denbigh

Nefyn

Penisarwaen

Cardiff Theosophical Society

in Wales

Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 1DL